Environment and Ecology, Science and Technology, Geography, Economics, Current Affairs, and Disaster Management.

The Big Issue

Plastic use has exploded with rising incomes and new markets. In 2024 alone, the world used about 500 million tonnes of plastics, creating roughly 400 million tonnes of plastic waste the same year. Only a small share is recycled; the rest is burned, landfilled, or leaks into nature. If current trends continue, global plastic waste could almost triple by 2060 to around 1.2 billion tonnes.

- Since 2000, global plastic production has doubled, reaching about 460 million tonnes by 2019. Plastics already account for about 3.4 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions across their life cycle.

- Every year, an estimated 11 million tonnes of plastics flow into the ocean, on top of vast amounts already circulating there.

Why plastics are a grave problem

Plastics do not biodegrade; they break into micro-plastics and nano-plastics that move through air, water, and soil, and can enter food chains. The climate cost is also rising.

- End-of-life today: Only about 9 percent of plastic waste is recycled; roughly half goes to landfills, about one-fifth is incinerated, and about one-fifth is mismanaged (open burning or leakage) — with higher leakage in poorer countries.

- Climate risk tomorrow: If nothing changes, the plastics life cycle could eat up a very large share of the remaining global carbon budget by 2040, making climate goals far harder to meet.

Where the waste comes from (and where it goes)

A few big flows explain the crisis.

- Short-lived uses: Packaging and disposable items dominate waste. Use is brief; waste lasts long.

- Leakage points: In many places, waste escapes formal systems — open dumps, burning, and river or ocean leakage. Without strong policy, mismanaged shares fall only slowly.

- Recycling gap: Even when collected, mixed materials, additives, and contamination make recycling difficult and costly, so most plastic does not become new plastic. The global recycling rate is stuck near 9 percent.

What the world is trying to do right now

Countries are negotiating a global, legally binding plastics treaty under the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee set up by the United Nations. Talks through 2024–2025 have not yet delivered a final deal, with debates on whether to cap virgin plastic output, control thousands of chemicals across the full life cycle, and how to finance action in developing countries.

Why a treaty matters: National bans and clean-ups help, but plastics are a global supply chain (oil wells to polymer plants to products to international waste trade). A treaty can set common rules on design, production limits, and waste management — so progress in one country is not undone by trade elsewhere.

What governments can do (priority actions that work)

Solutions must act across the entire life cycle — not just better dustbins.

- Design less and design better: Set targets to cut virgin polymer use; phase out problematic single-use items; mandate design for recycling and for reuse.

- Price the problem: Use producer-responsibility fees, deposit-return systems for bottles, and taxes on virgin resin so part of the cost shifts from cities to producers.

- Build systems, not dumps: Invest in segregation at source, material-recovery facilities, safe engineered landfills, and modern recycling — and formalise waste pickers who already recover large volumes.

- Stop leakage: End open dumping and burning; capture plastics in drains and rivers before they reach the sea.

- Use public purchasing power: Require recycled content in packaging and in public works such as roads.

- Measure and disclose: Create national plastics accounts (what is produced, imported, recycled, leaked) to guide policy and track progress.

What businesses and citizens can do

Small changes add up when they change demand.

- Move from single-use to systems: Refill and reuse models, bulk dispensers, and returnable transport packaging.

- Pick easier-to-recycle options: Clear bottles made of polyethylene terephthalate with peel-off labels; avoid multi-layer packs where good alternatives exist.

- Reduce, then recycle: Carry bottles, cups, and bags; refuse freebies you do not need; segregate clean plastics so recycling actually works.

- Cut litter at source: Keep drains clear; support local clean-ups; report illegal dumping.

- Back honest brands and policy: Prefer companies that disclose plastic footprints and fund producer-responsibility systems.

Exam Hook

Key takeaways

- Scale: Hundreds of millions of tonnes each year; recycling alone cannot catch up unless virgin plastic use falls.

- Leakage: About 11 million tonnes a year reaches oceans; stopping leakage needs system upgrades and enforcement.

- Climate link: Plastics are a growing source of emissions; action here also helps climate goals.

- Policy tools: Design rules, producer-responsibility fees, deposit-return systems, and recycled-content mandates deliver the fastest gains.

- Global coordination: A binding international treaty is essential to align production, trade, and waste rules.

Mains question:

“Global plastic pollution is a whole-of-life-cycle problem, not just a waste problem. Discuss

Hints : Critically analyse key levers — production caps, design for recycling and reuse, producer-responsibility fees, deposit-return systems, and recycled-content mandates — in the context of the ongoing United Nations plastics-treaty talks.”

One-line wrap

Use less plastic, design better products, capture all waste — and lock it into a global treaty.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

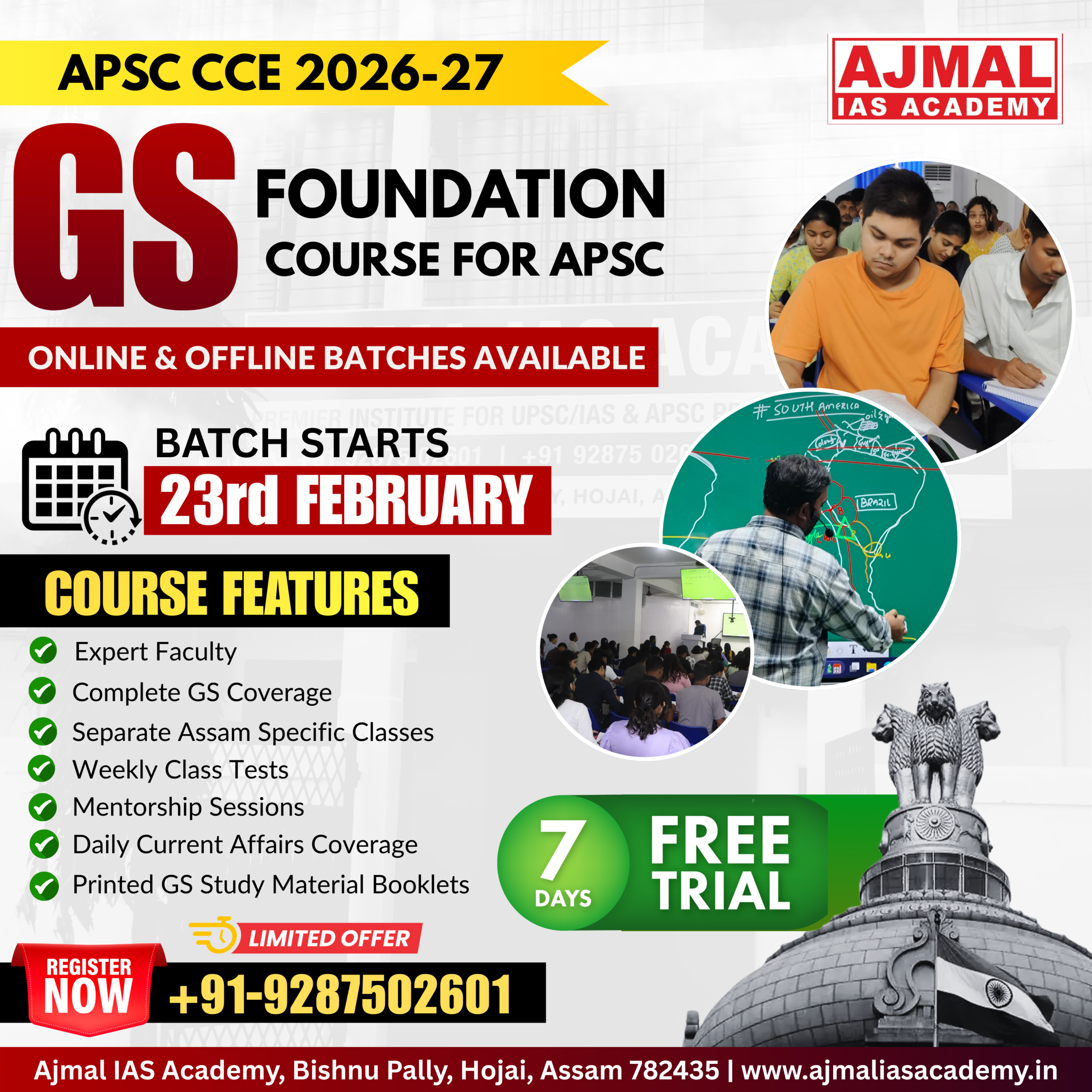

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.