Relevance (UPSC): GS-I (Indian Culture and Society), GS-II (Women, Social Justice)

What do women say about their own lives when tradition keeps them on the margins? India’s earliest answers come from the Therigatha—the “Verses of the Elder Nuns”—a luminous collection of poems in Pali where Buddhist nuns speak in their own voice about choice, grief, lust, freedom and peace. These verses, preserved in the Sutta Pitaka’s Khuddaka Nikaya, were recited for centuries before being written down. They record women—poor and rich, widows and courtesans—who walked away from fear and found a path to self-knowledge.

Ancient India knew other female voices too. The Brihadaranyaka Upanishad narrates Gargi’s fearless questioning in the royal court and Maitreyi’s dialogue with Yajnavalkya on love and immortality. These are not footnotes; they are proof that reason and renunciation were not gendered virtues.

Yet history also shows how this freedom was fenced. Later Dharmashastra literature tightened control over women’s mobility and sexuality. By the early medieval era, terms like svatantra stree (autonomous woman) were recast with suspicion. Commentaries such as Vigyaneshwara’s Mitakshara systematised a patriarchal household, even while acknowledging women’s limited property claims. Over time, marriage, kinship and caste pressed women into fixed social roles.

A long arc of silencing—and resistance

In the twentieth century, Gandhi’s satyagraha drew women into public life in large numbers. Peasant and tribal movements saw women as organisers and fighters. After Independence, law and policy expanded rights—inheritance reforms, dowry prohibition, the Maternity Benefit framework, and later the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005 and the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013. Schemes like One-Stop Centres, Nirbhaya Fund, and Beti Bachao Beti Padhao built support systems.

But a quieter silencing still operates. Popular culture prescribes the “ideal” face and body; the market sells “acceptability”; and politics often re-centres women only as mothers and homemakers. In homes and offices, unpaid care, time poverty and safety costs reduce real freedom. Online spaces amplify harassment, while courtroom and police processes can be intimidating.

Reading the Therigatha today is startling because the nuns speak without filters: “I have overcome my anger and lust… now, under a tree, I sit in peace.” They do not seek permission to think. The question for our time is: how do we translate that inner freedom into public equality?

What the State and society must do—

- Put safety and dignity first

- Enforce the sexual-harassment law beyond offices—Local Complaints Committees must work in every district.

- Fast, trauma-informed investigation in crimes against women; witness protection where needed.

- Enforce the sexual-harassment law beyond offices—Local Complaints Committees must work in every district.

- Recognise and redistribute care

- Expand creches, community childcare and safe transport; count unpaid care in time-use surveys; design urban services for caregivers.

- Expand creches, community childcare and safe transport; count unpaid care in time-use surveys; design urban services for caregivers.

- Guarantee economic rights

- Close the gender pay gap under the Code on Wages; support women’s collectives, self-help groups and entrepreneurship with credit, markets and digital payments; ensure equal inheritance on the ground.

- Close the gender pay gap under the Code on Wages; support women’s collectives, self-help groups and entrepreneurship with credit, markets and digital payments; ensure equal inheritance on the ground.

- Make digital spaces livable

- Stronger action against online stalking and image abuse; platform duty to cooperate; school curricula on online safety.

- Stronger action against online stalking and image abuse; platform duty to cooperate; school curricula on online safety.

- Listen to women’s own words

- Use community consultations to shape policing, transport, health and housing; publish disaggregated data so citizens can see progress.

- Use community consultations to shape policing, transport, health and housing; publish disaggregated data so citizens can see progress.

Key Terms

- Therigatha: Early Buddhist poems by elder nuns that speak of struggle and liberation; part of the Pali Canon.

- Bhikkhuni: A fully ordained Buddhist nun; early India had such orders before they declined.

- Svatantra stree: Literally “autonomous woman”; a contested idea in medieval legal-religious writing.

- Mitakshara: A classic Sanskrit legal commentary by Vigyaneshwara; influential for Hindu family and property law.

- Satyagraha: Truth-based non-violent resistance that drew women into public protest.

- Time poverty: Having so much unpaid care and domestic work that little time remains for paid work, rest or learning.

Why this matters

Culture is not just temples and textiles; it is voice. When you connect ancient women’s texts, constitutional rights and today’s policy tools, your answer shows continuity from inner freedom to public equality. Use sources like Therigatha, Upanishads, Bhakti and Sufi poetry, and pair them with Articles 14, 15, 16 and 21, and with modern laws named above. Add one grass-roots example—self-help group enterprises, women farmers’ cooperatives, a city with working helplines—and your answer moves from ideal to implementable.

Exam hook

“From Therigatha’s self-possessed voice to today’s helpline and creche, real freedom is inner dignity plus public infrastructure.”

Key takeaways

- India has a deep archive of women’s voices—Therigatha, Gargi, Maitreyi—often forgotten by later patriarchy.

- Modern law offers strong protections; implementation gaps and care burdens mute rights.

- Policy must combine safety, care services, economic opportunity, and digital protection.

- Cultural narratives should show women as thinkers, workers and citizens, not only as mothers.

Using in the Mains Exam

- Start with an ancient voice (Therigatha/Gargi), bridge to constitutional guarantees (Equality and Life with Dignity), then propose governance steps: Local Complaints Committees, creches, equal pay enforcement, platform accountability, time-use data.

- Conclude with a rights-plus-care sentence: freedom needs services.

UPSC Mains question

“Indian culture preserves women’s voices from the Therigatha to the Bhakti poets, yet public life still imposes silence.” Examine how law, markets and social norms interact to shape women’s agency. Suggest governance reforms. (250 words)

UPSC Prelims question

With reference to Indian culture, consider the following statements:

- The Therigatha forms part of the Khuddaka Nikaya of the Sutta Pitaka.

- Gargi and Maitreyi are women philosophers mentioned in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

- Vigyaneshwara’s Mitakshara is a medieval commentary that influenced Hindu family law traditions.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

(a) 1 only (b) 1 and 2 only (c) 2 and 3 only (d) 1, 2 and 3

Answer: (d)

One-line wrap

Let the old verses guide new policy—so that every woman’s voice travels from the home and the screen to the street and the State.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

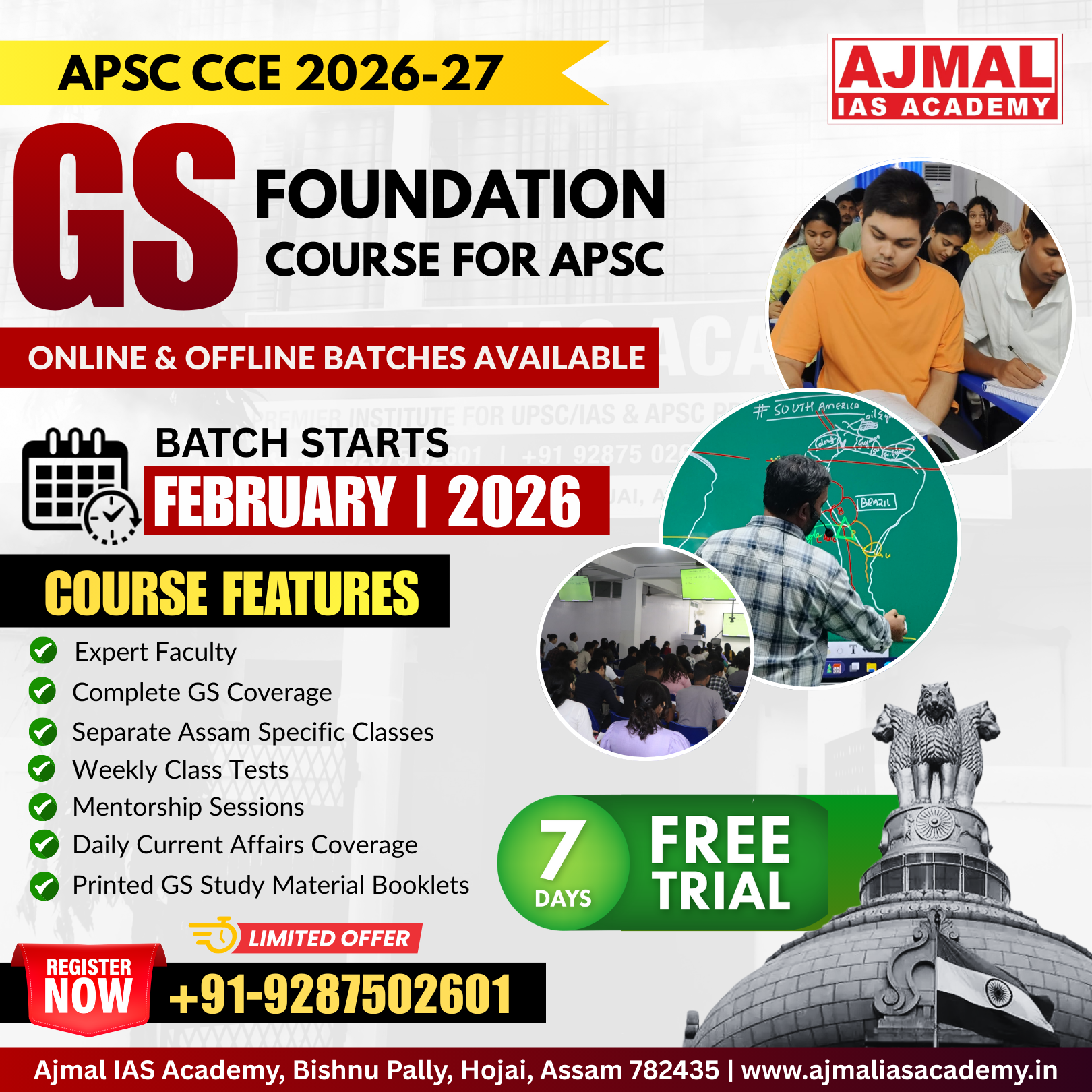

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.