Q.8 How does a smart city in India address the issues of urban poverty and distributive justice? (Answer in 150 words)

Intro

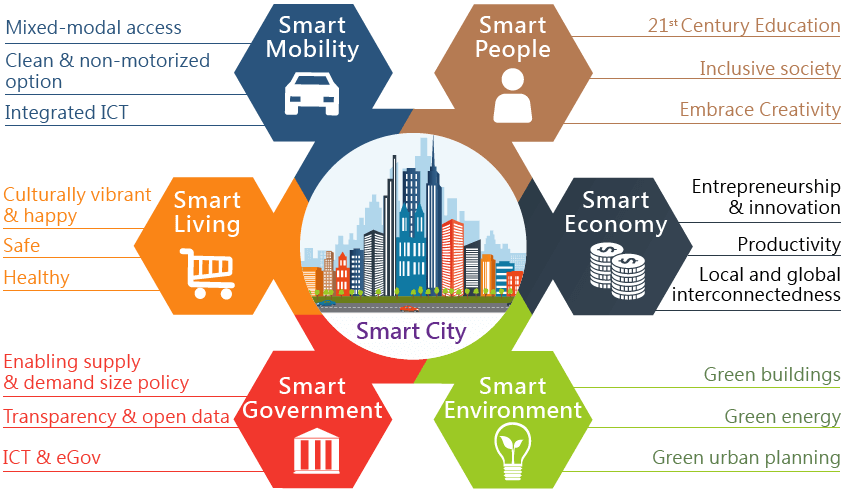

The Smart Cities Mission (2015–) pursues better basic services, liveability, and governance using data, design, and convergence. Distributive justice implies fair access to housing, services, mobility, safety, and opportunities—especially for the urban poor.

Key Features of Smart Cities

- Core Services – 24×7 water, electricity, sanitation, affordable housing, and efficient waste management.

- Smart Governance – ICT-based e-governance, online services, grievance redressal, and smart meters/surveillance.

- Sustainability – Solar rooftops, LED lighting, rainwater harvesting, recycling, green spaces, and pollution monitoring.

- Mobility – Smart traffic systems, integrated public transport, EV promotion, and pedestrian/cycling tracks.

- Economy & Livelihoods – Skill centres, startup hubs, local industry promotion, and PPP models.

- Safety & Inclusivity – CCTV, emergency response systems, women- and elderly-friendly public spaces, and barrier-free access for the disabled.

How it addresses poverty & promotes distributive justice

- Basic services first: 24×7 water, sanitation, solid waste, universal public toilets (ODF++), and last-mile connections in informal areas.

- Affordable, proximate housing: In-situ slum upgrading/ISSR and PMAY-U convergence; rental/hostel models for migrants.

- Mobility for inclusion: Footpaths, NMT, e-buses, BRT, integrated tickets—reduces time & cost burdens on wage workers.

- Livelihoods & informality: Vending zones, night markets, skill centres; linkages to DAY-NULM/PM-SVANidhi.

- Digital public infrastructure: One-stop service centres, open data portals, grievance apps; targeted benefits via DBT.

- Safe, gender-responsive public realm: Lighting, CCTV with protocols, women-only helpdesks, child-friendly spaces.

- Urban commons & climate resilience: Lakes, parks, mangroves restored to buffer heat/floods where poor live.

Examples

Indore (waste & livelihoods of safai mitras), Pune (participatory budgeting; e-bus fleet), Bhubaneswar (child-friendly design), Surat (flood resilience, BRT), Bhopal (integrated command centre for emergency response).

Caveats / Critique

- Area-Based Development enclaves risk gentrification.

- Digital divide may exclude those without devices/skills.

- SPV accountability and user charges can burden the poor.

Way forward

Scale pan-city solutions, mandate pro-poor service standards, protect tenure/vending rights, embed social audits & gender budgeting, and align with climate-resilient low-income housing.

Conclusion

Smart cities can advance distributive justice when tech and design are anchored in rights, participation, and affordability—not just aesthetics.

Q.9 The ethos of civil service in India stands for the combination of professionalism with nationalistic consciousness – Elucidate. (Answer in 150 words)

Intro

India’s civil services were envisioned as a competent, impartial “steel frame” as per Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel—yet animated by constitutional patriotism: loyalty to the sovereignty, integrity, and welfare of all citizens.

Professionalism: features

- Competence & neutrality: Evidence-based policy, SOPs, due process, financial propriety.

- Service orientation: Citizen charters, e-governance, RTI responsiveness.

- Capability building: LBSNAA/IGOT-Karmayogi, domain specialisation, disaster management skills.

- Performance in missions: Swachh Bharat, Jal Jeevan, health campaigns, elections—time-bound, metric-driven delivery.

Nationalistic consciousness: meaning

- Constitution-anchored patriotism: Upholding FRs/DPs, unity in diversity, last-mile inclusion.

- Nation-building roles: Integrating frontier/Left-Wing-Extremism/tribal areas through welfare, infrastructure, and law & order with sensitivity.

- Crisis stewardship: Cyclones, floods, pandemics—duty beyond self; integrity under pressure.

Balancing act (ethics)

- Guard political neutrality while serving democratic mandates.

- Prefer the rule of law over personality cults; safeguard minorities and vulnerable groups.

- Manage conflicts of interest, resist policy capture, protect whistle-blowers.

Examples

Aspirational Districts outcomes, election management, rapid disaster relief, direct benefit transfers, curbing leakages.

Way forward

Some committees like 2nd ARC suggested a few measures like : Merit-based postings, lateral entry where needed, ethical codes with consequence management, citizen feedback loops, and data-governed but humane administration.

Conclusion

The Indian civil service best serves the nation when technical excellence is fused with constitutional devotion—competence with conscience.

Q.10 Do you think that globalization results in only an aggressive consumer culture? Justify your answer. (Answer in 150 words)

Introduction

Globalization is the intensification of flows of goods, capital, people, data, and ideas. While it has undeniably strengthened consumerism, to see it only as an “aggressive consumer culture” is partial. It also enables knowledge exchange, cultural fusion, and cooperative solutions to global challenges.

Consumerist Impacts

- Mc Donaldisation: Coined by George Ritzer, it captures the spread of uniform, fast, efficient, but predictable services—fast-food chains, malls, multiplexes—that standardise taste and culture, weakening local diversity.

- Walmartisation: The expansion of global retail giants and “one-stop low-cost” chains undercuts small retailers and kirana shops, creating a culture of bulk buying, discount-driven consumption, and homogenised goods.

- Predatory pricing: Global e-commerce platforms (e.g., Amazon) use deep discounting and data-driven monopolistic practices to drive out local competition. This fosters consumer dependency but undermines market diversity.

- Fast fashion & obsolescence: Rapid trend cycles, influencer marketing, and planned obsolescence generate wasteful consumer aspirations with ecological costs.

- Cultural homogenisation: Mass adoption of global brands erodes traditional producers, crafts, and food systems.

But Globalization Is Not Only Consumerism

- Idea flows: Norms of human rights, democracy, environmentalism, gender equality spread globally.

- Tech diffusion: Smartphones, fintech, telemedicine, and e-learning democratise access.

- Cultural hybridisation: Local meets global—glocal food chains, K-pop in India, Yoga and Ayurveda abroad, GI-tag crafts entering export markets.

- Development linkages: Remittances, global value chains, diaspora networks (e.g., Indian IT professionals in Silicon Valley), and global climate/pandemic cooperation.

- Counter-cultures: Global platforms also promote minimalism, slow fashion, fair trade, circular economy—challenging the very consumerism they spread.

India-Specific Illustrations

- IT & Pharma services dominate exports; India’s UPI inspires adoption abroad.

- Yoga, Ayurveda, millets, and Indian cinema/OTT build cultural exports.

- Risks: Online deep discount wars hurt small retailers (predatory pricing), cheap imports undermine artisans, and fast fashion raises e-waste.

Risks to Manage (Hidden Demand)

- Inequality & labour precarity: Gig work, unsafe supply chains.

- Monopoly capitalism: Predatory pricing and algorithmic bias concentrate power.

- Environmental costs: Carbon footprints, e-waste, unsustainable agriculture.

- Cultural erosion: Loss of indigenous foods, crafts, languages.

- Data colonialism: Exploitation of user data by global tech platforms.

Way Forward

- Regulatory frameworks: Anti-monopoly laws, predatory pricing checks, Front-of-Pack labelling for health, labour rights in global supply chains.

- Support local industries: Incentivise MSMEs, handicrafts, creative economies, “Vocal for Local” campaigns with fair digital platforms.

- Sustainable consumerism: Circular economy, extended producer responsibility (EPR) for packaging, eco-certifications.

- Educated consumption: Media and financial literacy to build critical awareness among consumers.

Conclusion

Globalization has indeed produced McDonaldised and Walmartised consumer cultures, and predatory pricing threatens diversity. Yet, it also diffuses rights, science, culture, and solidarity. The challenge is not whether globalization is “good” or “bad,” but how it is shaped by policy and civic choices. With sustainability, equity, and cultural pluralism, globalization can be a source of enrichment rather than erosion.

Q.17 Discuss the distribution and density of population in the Ganga River Basin with special reference to land, soil and water resources. (Answer in 250 words)

Introduction

The Ganga basin, covering ~26% of India’s area and supporting over 40% of its population (~520 million, Census 2011), represents both an opportunity and a stress point. Its density patterns are not random; they reflect a systematic interaction between physiography, soils, and water availability. The contrast is sharp—<300 persons/km² in Himalayan headwaters versus >1,000 persons/km² in alluvial plains and delta.

Analytical Spatial Logic

- Himalayan headwaters (Uttarakhand)

- Cause: Rugged relief, landslide risks, shallow soils.

- Effect: Sparse, scattered villages (200–350/km²) and out-migration despite abundant streams.

- Terai–Bhabar belt

- Cause: New alluvium, high water tables, level relief.

- Effect: Higher densities (800–1,000/km²) with rice–wheat, dairying, and groundwater irrigation.

- Ganga–Yamuna Doab (W. U.P.)

- Cause: Deep loamy soils + canal–tubewell irrigation (Upper Ganga Canal).

- Effect: Among the densest rural zones (Meerut >1,200/km²), sustaining sugarcane–wheat and peri-urban sprawl.

- Middle Ganga Plain (E. U.P.–Bihar)

- Cause: Fertile “new alluvium,” but frequent floods (Ghaghara, Gandak, Kosi).

- Effect: Bihar’s density ~1,100/km²; high settlement on levees, but seasonal migration due to floods and arsenic in groundwater.

- Lower Ganga–Hooghly Plain & Delta (W. Bengal)

- Cause: Clayey soils, water abundance, navigable rivers, port access.

- Effect: West Bengal avg. 1,029/km², with Kolkata exceeding 24,000/km²—a blend of rural crowding and urban-industrial pull.

Why Density Is High Overall

- Agricultural logic: Fertile alluvium (khadar/bhangar) + multi-crop potential + canal–groundwater grids sustain populations 2–3× India’s national average (382/km²).

- Cultural magnets: Pilgrimage and trading hubs (Varanasi, Prayagraj) anchor populations.

- Connectivity: Flat terrain + riverine corridors historically eased mobility and trade.

Challenges of High Density (Analytical Risks)

- Hydro-hazards: Bihar alone sees ~8 million people flood-affected annually—densities amplify exposure.

- Resource stress: Over-extraction → falling groundwater; arsenic/fluoride contamination in >20 districts.

- Soil stress: ~30% of canal-irrigated U.P. land faces waterlogging/salinity, reducing productivity per capita.

- Urbanisation pressures: Kolkata’s 14 million population → solid waste, housing deficits, heat islands.

- Livelihood fragility: Land fragmentation and disguised unemployment in Bihar–E. U.P. trap surplus labour.

Way Forward

- Risk-aware planning: Floodplain zoning, early warning, embankment management.

- Water security: Conjunctive use of canal + aquifers, recharge projects, safe piped supply in arsenic zones.

- Soil & farming: Crop diversification (pulses, oilseeds), micro-irrigation, soil health restoration.

- Urban resilience: Protect wetlands, manage solid waste, and adopt compact, transit-oriented growth.

- Livelihood shifts: Skill development, rural non-farm clusters, and climate-risk insurance.

Conclusion

The Ganga basin illustrates how fertility, water, and flat land attract people—but densities often exceed 1,000/km², magnifying risks. Sustaining this heartland requires shifting from growth-by-density to resilience-by-design, balancing population pressures with risk management, ecological security, and equitable livelihoods.

Q18. How do you account for the growing fast food industries given that there are increased health concerns in modern society? Illustrate your answer with the Indian experience. (Answer in 250 words)

Introduction

The paradox is structural: on the demand side, time-poverty, convenience, and the pull of “McDonaldization” (standardised, fast, predictable services) shape choices. On the supply side, economies of scale, localised menus, and app-based delivery platforms make fast food more available and affordable. Together, these forces outweigh rising health anxieties.

Why Growth Continues

- Demand-side drivers

- Urbanisation & dual-income homes: Less cooking time → more reliance on quick meals.

- Youth demographics & aspiration: Fast food = socialising + modern identity; salt–sugar–fat tastes ensure repeat demand.

- Perceived hygiene: Chains appear safer than informal stalls.

- Delivery apps & UPI: Easy ordering, discounts, combos, and gamified loyalty schemes push consumption.

- Supply-side accelerants (India examples)

- Localization: McAloo Tikki, paneer wraps, Jain menus, millet options.

- Deep reach: Domino’s, Subway, desi QSRs like Haldiram’s, Wow! Momo, biryani brands expanding into tier-2/3 cities.

- Cloud kitchens: Reduce cost, run multiple brands from one kitchen, extend hours.

- Cold chain & commissaries: Ensure stable quality, large-scale operations.

Challenges of Fast-Food Boom (hidden demand)

- Public health: Non-communicable diseases (obesity, diabetes, hypertension); aggressive child marketing.

- Behavioural traps: Portion upsizing, discounts, BNPL schemes → overconsumption.

- Environment: Single-use plastic packaging, fryer-oil disposal, delivery vehicle emissions.

- Food systems: Dependence on processed oils/inputs, decline of local nutritious foods.

- Labour/urban issues: Precarious gig work; traffic congestion around dense outlets.

Way Forward

- Policy & regulation:

- Front-of-Pack Labelling (FoPL), tax sugary drinks, restrict HFSS ads to children.

- Mandatory healthy canteens in schools/offices; zoning caps near schools.

- Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for packaging; norms for oil reuse; electric fleets.

- Industry:

- Reformulate for less salt/sugar, smaller default portions, calorie transparency.

- Scale healthy Indian fast-casual formats (idli/dosa, poha, millet bowls).

- Platforms & consumers:

- “Healthy choice” badges/filters on apps; baked instead of fried swaps; digital nutrition nudges.

Conclusion

Fast food’s rise in India is ecosystem-driven, not a passing fad. Balancing convenience with health, environment, and livelihoods requires smart regulation, industry redesign, and promotion of nutritious Indian quick foods.

Q19. Achieving sustainable growth with emphasis on environmental protection could come into conflict with poor people’s needs in a country like India – Comment. (Answer in 250 words) 15

Introduction (2–4 lines)

In India, environmental protection often appears to conflict with the poor’s basic needs—land for farming, forests for fuel, water for daily use, or jobs from industries. This tension is less an inevitable trade-off and more a result of policy design: when conservation excludes livelihoods, it breeds conflict; when integrated with welfare, it creates co-benefits.

Where conflicts arise (India lenses)

- Land & commons: Protected areas/riverfront “rejuvenation” and CRZ restrictions can curb forest/fishing/livestock livelihoods; eviction risks if FRA/PESA are weakly implemented.

- Energy transition: Coal phase-down threatens jobs in coal belts; clean cooking/electricity can be costly to sustain without refill/usage support.

- Pollution control & MSMEs: New norms raise compliance costs for small units, risking closures and informal job loss.

- Mining/infrastructure siting: Bans or stoppages protect ecology but remove local income; conversely, permissive siting can harm health and water.

- Agriculture & water: Groundwater caps, input restrictions, or stubble-burning bans hit smallholders lacking affordable alternatives.

- Urban poor: “Green beautification” may justify slum demolitions instead of in-situ upgradation.

- Subsidies like free electricity and cheap fertilizers support marginal farmers but also drive overuse of water, soil depletion, and pollution, creating a conflict with environmental protection.

Hidden demand: challenges + way forward

Challenge: Transition Costs

- Upfront expense: Poor households lack savings to invest in green options like solar pumps, drip irrigation, or clean cookstoves.

- Cash-flow constraints: Even subsidised technologies demand some upfront payment, which is unaffordable for daily-wage families.

- Information gaps: Limited awareness of schemes, technical know-how, and long-term benefits of eco-friendly alternatives.

- Weak voice in planning: Decisions on siting renewable parks, conservation zones, or infrastructure are top-down, with little local consultation.

- Risk of exclusion: Without targeted finance, credit access, and community participation, the poor may be left behind in the green transition.

Way forward (co-benefit design):

- Just Transition for coal regions (reskilling, MSME parks, social protection) using DMF/CESS funds; community stake in renewable parks.

- Rights-based conservation: Full FRA/PESA compliance, Gram Sabha consent/benefit-sharing, Payments for Ecosystem Services; community co-management (NTFP value-add, eco-tourism).

- Affordable clean energy: Lifeline tariffs, targeted subsidies for LPG refills/PNG, solarised irrigation with caps, reliable power to reduce diesel dependence.

- MSME green upgrade: Cluster CETPs, concessional green credit, common retrofits (boilers, scrubbers).

- Farmer support: Crop diversification (pulses/millets), micro-irrigation, residue management support, climate insurance.

- Urban inclusion: In-situ slum upgrading, blue-green infrastructure that creates local jobs; safeguard relocation only as last resort.

Conclusion (1–2 lines)

Sustainability need not undercut poverty goals. With justice-centred design—rights, compensation, participation, and co-benefits—India can align green protection with the daily economics of the poor.

Q.20 Does tribal development in India centre around two axes, those of displacement and of rehabilitation? Give your opinion. (Answer in 250 words)

Introduction

Since Independence, over 85 lakh tribal people have faced displacement due to dams, mines, industries, and conservation projects (Ministry of Tribal Affairs). Displacement-induced development has been the dominant paradigm, but responses have mostly centred on Resettlement & Rehabilitation (R&R)—often delayed and inadequate.

Why it looks displacement-centric (with examples & evidence)

- Project drivers:

- Dams: Sardar Sarovar Project displaced thousands, triggering the Narmada Bachao Andolan led by Bhil and Gond communities.

- Mining: Niyamgiri hills saw resistance from Dongria Kondh tribes against bauxite mining (Vedanta).

- Large dams: Polavaram project caused displacement of Chenchu tribes in Andhra Pradesh.

- Tiger reserves and conservation zones restricted access to forests, grazing, and fuelwood.

- R&R practice:

- Cash compensation in place of land/commons, often inadequate.

- Weak Gram Sabha consent under PESA and tick-box social impact assessments.

- Livelihood restoration lags far behind physical relocation.

- Outcomes:

- Land alienation and loss of traditional control over forests.

- Rising extreme poverty; tribal poverty levels consistently above national average.

- Low literacy (only ~49% as per Census 2011, vs. national 74%) limits alternatives.

- Cultural erosion—rituals, sacred groves, and community networks disrupted.

Beyond displacement: Rights-based turn

- PESA (1996): Gram Sabha powers in Schedule V areas (minor minerals, local plans, customs).

- FRA (2006): Individual & community forest rights—potential for NTFP-based livelihoods.

- Resource sharing: District Mineral Foundation (DMF), MSP for minor forest produce, Van Dhan Kendras, EMRS schools, mobile health services.

Gaps: Slow CFR recognition, elite capture of DMF, culturally misaligned welfare schemes, fragile nutrition among PVTGs.

Hidden Demand: Challenges + Way Forward

- Challenges: Project-first siting, tokenistic consent, compensation ≠ livelihood security, erosion of territorial/cultural rights.

- Way Forward:

- Minimise displacement through alternative alignments/technologies.

- Make FPIC (Free, Prior, Informed Consent) and Gram Sabha powers substantive.

- R&R as livelihood restoration—land-for-land, access to commons, annuities, skill pathways.

- Secure rights & self-governance: speedy CFR recognition, participatory DMF with audits.

- Culturally sensitive services: mother-tongue education, nutrition kitchens, community-based health.

- Measure success by income, literacy, health, and ecological outcomes, not just cheques distributed.

Conclusion

Tribal development in India has too often been reactive to displacement. A durable path must centre rights, consent, and livelihood sovereignty, with R&R as a last resort. Only by aligning development with tribal dignity, culture, and ecological balance can India ensure inclusive growth.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.