Relevance: GS-2 (Polity – Constitutional Offices, Federal Relations)

Source: The Hindu; Constituent Assembly Debates (CAD); Supreme Court Judgments (2023–25)

The Debate on Governor’s Powers Resurfaces

A recent Supreme Court observation on delays by Governors in granting assent to Bills has reignited debate on the scope, limits, and spirit of the Governor’s office. The controversy has revived deeper questions discussed in the Constituent Assembly—whether a nominated Governor can truly be impartial, and what role the Constitution actually envisages for the office.

What the Framers Intended: A Limited Constitutional Governor

During the Constituent Assembly debates (1947–49), many members feared that a nominated Governor, appointed by the Centre, could become a “replica of the colonial Viceroy.”

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar addressed these concerns directly:

- The Governor is not an agent of the Centre.

- He is to act only on the aid and advice of the State’s Council of Ministers (Articles 154, 163).

- Discretionary powers are specific, exceptional, and not a parallel authority.

- The Governor is meant to be a neutral constitutional head, not an elected political rival to the Chief Minister.

Ambedkar repeatedly reassured members:

“The Governor will have no independent authority. His role is formal and constitutional.”

Why the Debate Continues: Contemporary Tensions

A. Assent to Bills and Legislative Delays

Recent disputes in Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Punjab and Telangana highlight Governors withholding Bills or reserving them for the President without explanation.

The Supreme Court has clarified:

- Governors must act expeditiously.

- They cannot “sit on” Bills indefinitely.

- Their discretion must be narrowly interpreted, consistent with constitutional morality.

B. Misreading Discretionary Powers

Ambedkar warned against assuming that discretion equals independent power.

However, political misuse—real or perceived—has led States to view Governors as extensions of the Centre.

C. The Core Federal Dilemma

- States argue Governors are bypassing democratic mandates.

- Centre argues Governors ensure constitutional compliance.

- Courts emphasise constitutional restraint and the need for swift, reasoned action.

The tension stems not from the Constitution, but from practice diverging from intended conventions.

The Way Ahead: Restoring Constitutional Correctness

- Define timelines for assent, return, or reservation of Bills.

- Institutionalise conventions (as in Westminster systems) to guide Governor–State interaction.

- Mandate written reasons when reserving or withholding Bills.

- Induction-level training for Governors on constitutional morality and federal balance.

- Strengthen cooperative federalism forums, such as the Inter-State Council, for dispute resolution.

Impartiality is built into the Governor’s constitutional role—its erosion stems from practice, not constitutional architecture.

UPSC Mains Question

“Discuss the constitutional position of the Governor. Why do conflicts continue between Governors and State governments despite the framers’ clear intent?”

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

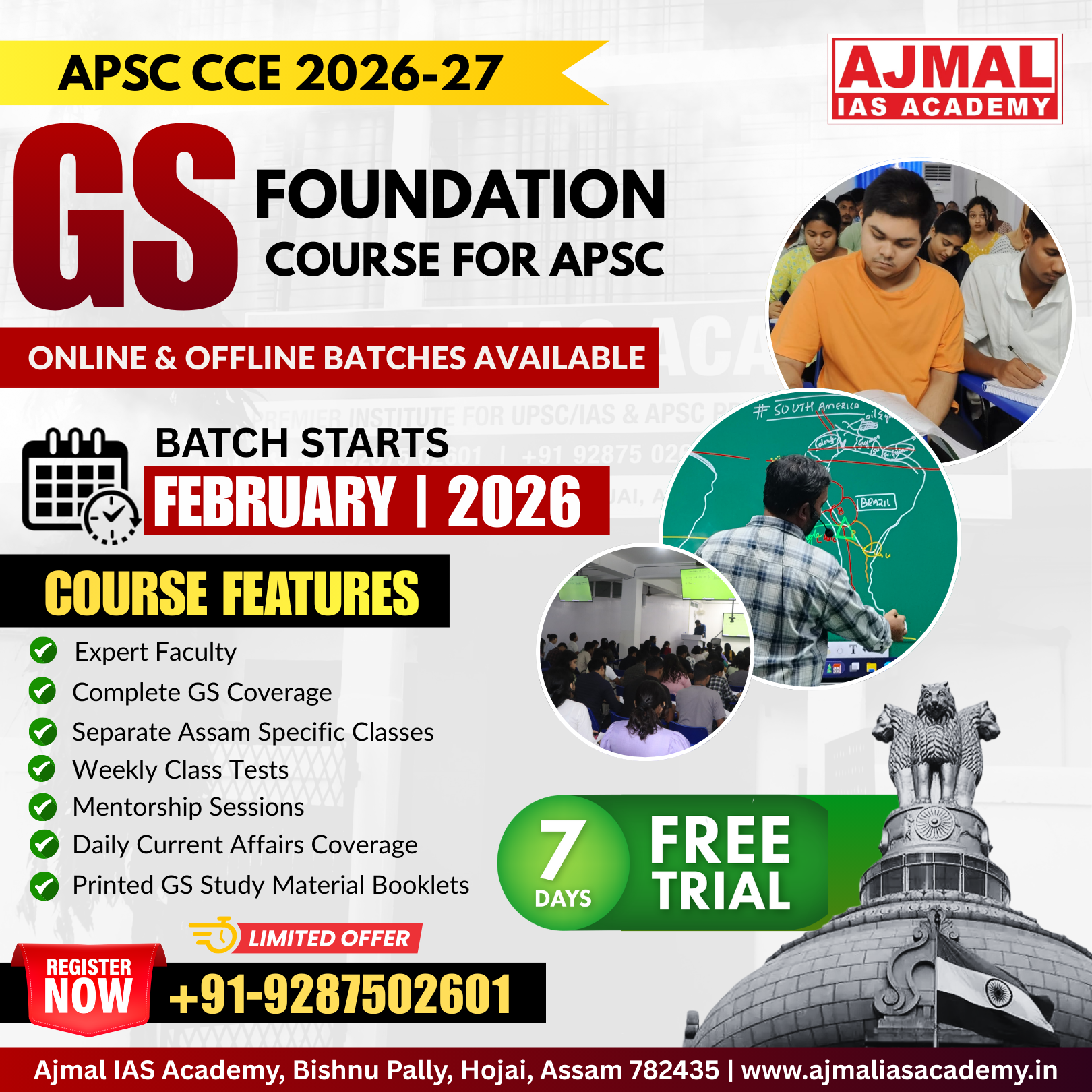

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.