Relevance: GS Paper II (Polity – Judiciary: Independence vs. Accountability)

Source: The Hindu

Context

The issue of judicial accountability is back in the spotlight. In December 2025, 107 MPs submitted a motion to remove Justice G.R. Swaminathan of the Madras High Court on charges of “acting against secular principles.” The motion is currently sitting with the Lok Sabha Speaker, who holds the power to admit or reject it—a discretionary power that experts call a “major legal loophole.”

Constitutional Basics (The Rulebook)

- Terminology: The Constitution uses “Removal” for Judges (Article 124/217) and “Impeachment” only for the President (Article 61). However, in common parlance, we use “impeachment” for both.

- Grounds: A judge can be removed only for:

- Proved Misbehaviour (Conduct that brings dishonor/wilful abuse of office).

- Incapacity (Physical or mental inability).

- Note: A wrong judgment or simple negligence is not misbehaviour (K. Veeraswami Case).

The Process: A “Triple Lock” System

To protect judges from political vendetta, the Constitution and the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968 created a rigorous 3-step fortress:

- The Trigger: A removal motion must be signed by 100 MPs (Lok Sabha) or 50 MPs (Rajya Sabha) and submitted to the Presiding Officer (Speaker/Chairman).

- The Investigation: If admitted, a high-power 3-Member Committee (SC Judge + HC Chief Justice + Jurist) investigates the charges.

- The Verdict: If found guilty, both Houses of Parliament must pass the motion by a Special Majority (50% of total strength + 2/3rds present and voting) in the same session.

The “Loophole”: The Gatekeeper’s Discretion

This is the core analytical point.

- The Issue: The Judges Inquiry Act gives the Speaker/Chairman absolute discretion to admit or reject the motion at the very first step.

- The Conflict: The Constitution intended “investigation” to be a judicial task. However, the Act allows a political authority (Speaker) to block this investigation without giving detailed reasons.

- The Consequence: If a Speaker rejects a motion signed by 100 MPs (as happened in the Justice Dipak Misra case, 2018), the accountability process is killed before it even begins. It turns a “constitutional check” into a “political choice.”

UPSC Value Box

Historical Fact:

- Zero Removals: No judge has ever been successfully removed in independent India.

- Justice V. Ramaswami (1993): The inquiry found him guilty, but the motion failed in Parliament because the ruling party abstained.

- Justice Soumitra Sen (2011): He resigned after the Rajya Sabha passed the motion but before the Lok Sabha vote, avoiding the final tag of removal.

Analytical Insight:

The current system struggles to balance Independence (tenure security) with Accountability (punishing bad apples).

Reform Needed: The decision to admit a motion should be based on legal merit, not political will. A permanent National Judicial Oversight Committee could replace the Speaker’s discretion at the admission stage.

Summary

While India has a robust mechanism to remove judges for misconduct, the Judges Inquiry Act, 1968 contains a critical flaw: it empowers the Speaker to act as the sole gatekeeper. By allowing a political authority to reject a removal motion at the threshold, the law risks prioritizing political convenience over judicial integrity.

One Line Wrap: We have a “secure” judiciary, but the path to “accountable” justice is often blocked at the entry gate.

UPSC Mains Question

Q. “The legislative procedure for the removal of judges attempts to balance independence with accountability, but statutory loopholes often tilt the scale.” Discuss in light of the Judges (Inquiry) Act, 1968. (10 Marks, 150 Words)

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

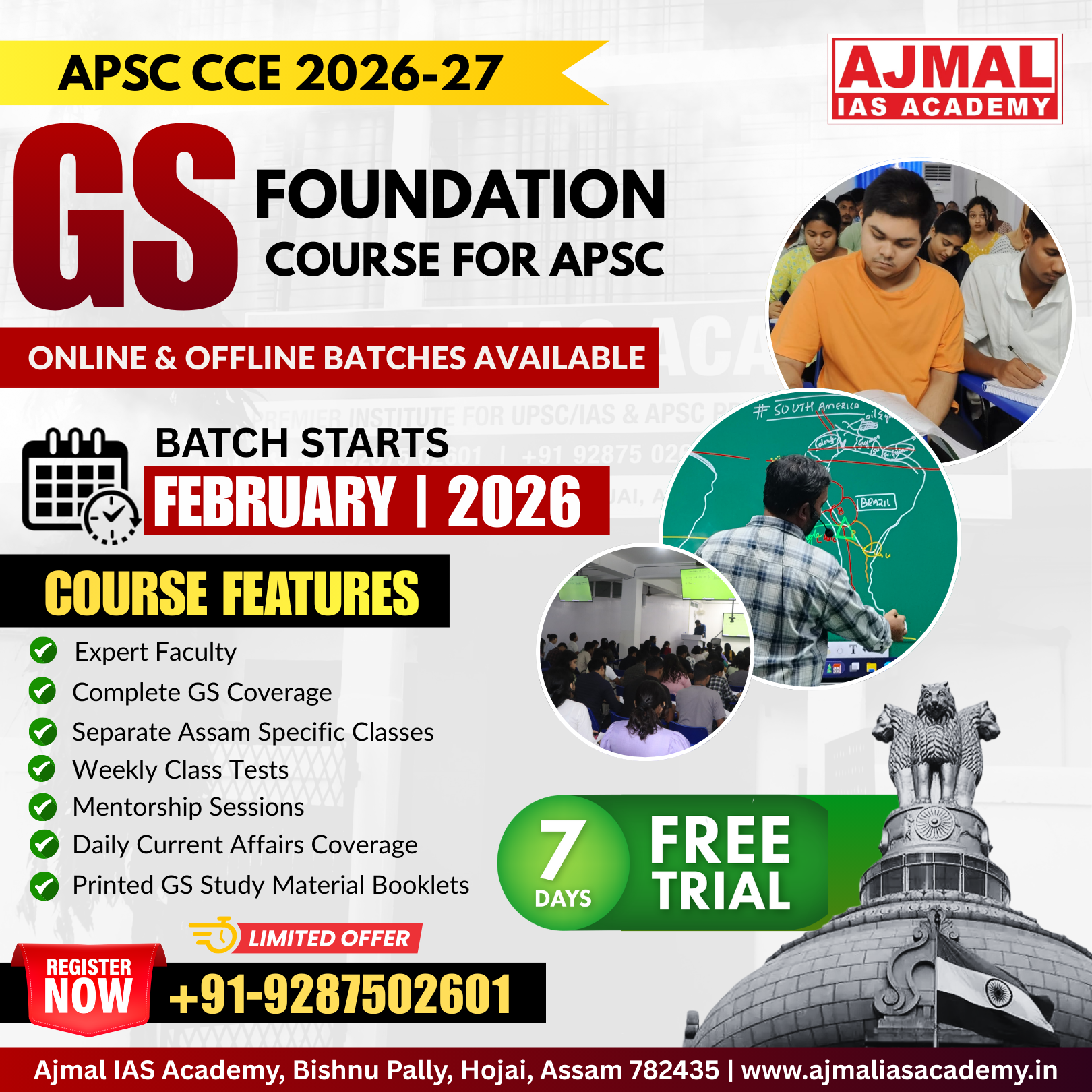

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.