Relevance (UPSC): GS-II (Polity & Governance), GS-I (Society), GS-III (Social Justice & Labour)

India’s homes are also workplaces. Cooks, cleaners, live-in caregivers, drivers and child-minders keep cities running, yet their work is mostly invisible in law. Courts have lately asked the Union government to consider a comprehensive national framework for domestic workers. Several States have welfare boards and minimum-wage orders, but coverage is patchy. A clear, humane central law can convert routine dependence into recognised work with rights.

The people behind the work

- Estimates place domestic workers anywhere between four million and ninety million. A large share are women and many belong to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes or migrant communities.

- Employment is informal: oral contracts, variable hours, and cash payments. Live-in workers face the highest risks—overwork, surveillance, unpaid overtime, and isolation.

- Placement agents and brokers often sit between households and workers, creating room for exploitation and trafficking.

What the law must fix

- No clear national definition of “domestic work”, “domestic worker”, “employer”, and “placement agency”.

- Uneven wages and hours—some States notify minimum wages, others do not; weekly rest and paid leave are rare.

- Weak social security—health insurance, maternity benefits, accident cover and old-age support are limited or absent.

- Safety and grievance redress—domestic workers are formally covered by the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, 2013 through District Local Committees, but access and awareness are uneven.

- Poor regulation of agencies—registration, due diligence and record-keeping are not uniform.

What a good central law should contain

Clear recognition and scope

- Legal status: Declare domestic work as work with rights, not “help”.

- Definitions: Cover live-in and live-out workers, full-time and part-time, caregivers, cooks, cleaners, drivers and gardeners.

- Child labour ban: Absolute prohibition on employment of children; strict penalties for trafficking.

Written, simple contracts

- One-page bilingual employment contract stating duties, place of work, wage, hours, weekly rest, paid leave, food and accommodation (if live-in), and termination rules.

- Digital or paper copy lodged on a free public portal or at ward offices.

Floor of labour standards

- Minimum wage (indexed to inflation), eight-hour standard, weekly day of rest, and paid leave.

- Maternity, health and accident cover through a pooled welfare fund.

- Overtime pay and a ban on withholding wages or identity documents.

Social security and portability

- A Domestic Workers Welfare Board in every State linked to a National Register for portability across cities.

- Benefits funded by budgetary support + a small employer contribution + a modest levy on placement agencies.

- Grievance helpline, time-bound conciliation, and easy compensation procedures.

Regulating placement agencies

- Mandatory licensing, background checks, receipts and payslips, and duty to explain contract terms to workers.

- Heavy penalties for deception, confinement, or charging recruitment fees to workers.

Safety and dignity

- Access to Local Complaints Committees under the sexual-harassment law; awareness drives in every ward.

- Rescue and shelter protocols for abuse cases; legal aid and counselling supported under social-justice schemes.

Simple enforcement

- Facilitation over raids: trained community facilitators and labour officers who resolve disputes and document contracts.

- Incentives for compliance: tax receipt for employer contributions; fast-track visas or clearances for verified care work.

Where India stands in global norms

The International Labour Organization Convention No. 189 on Domestic Workers sets standards on fair terms, social security, and decent work. Many countries have adopted laws based on it. India has not ratified the convention yet; a strong domestic law would bring us closer to its spirit.

Constitutional and policy anchors

- Article 21 (life with dignity), Article 23 (ban on forced labour), and Directive Principles on just and humane conditions of work support protective legislation.

- The Unorganised Workers’ Social Security framework and State welfare boards show a path, but need national coherence and portability.

Key Terms

- Domestic worker: A person employed in a home to perform tasks like cooking, cleaning, caregiving or driving, for pay.

- Live-in worker: Someone who resides at the employer’s home as part of the job; needs clear rules on hours, rest and privacy.

- Placement agency: A middle-person or company that recruits and places workers; must be licensed and accountable.

- Minimum wage: The legal lowest wage per hour or per month below which payment cannot fall.

- Written contract: A short, signed document listing duties, hours, wage and leave—your proof in case of disputes.

- Local Complaints Committee: A district-level body that hears sexual-harassment complaints from workers outside formal offices, including domestic workers.

Policy design in practice: a workable blueprint

- One nation, one simple contract, downloadable in all major languages.

- National Register with a digital worker card; no fee for registration.

- Welfare package: health cover, maternity benefit, accident insurance and pension micro-savings with a matching government share.

- City-level boards to set realistic local minimum wages and to run drop-in centres for counselling and skill training.

- Quarterly transparency: publish numbers on contracts registered, disputes settled, compensation paid, and agency licences granted or cancelled.

Exam hook

A central law can convert invisible, feminised, caste-marked labour into formal, protected work aligned with constitutional morality and global standards.

Key takeaways

- Recognise domestic work as work with rights; standardise contracts, wages, hours and weekly rest.

- Build portable social security via national and state registers and welfare boards.

- License and monitor placement agencies; protect against trafficking and child labour.

- Ensure safety and grievance redress through Local Committees and helplines.

- Keep enforcement simple, facilitative, and transparent.

Using in the Mains exam

Link Article 21/23, Directive Principles, Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act, Unorganised Workers’ Social Security architecture, and International Labour Organization Convention 189. Add one State example (for instance, a welfare board and notified minimum wages) to show feasibility.

UPSC Mains question

“Domestic work is essential care work but remains legally invisible.” Discuss the need, contours and implementation architecture of a national law for domestic workers, referring to constitutional principles and international standards. (250 words)

UPSC Prelims question

Q. With reference to protection of domestic workers in India, consider the following statements:

- The Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act allows domestic workers to file complaints before District Local Committees.

- International Labour Organization Convention No. 189 deals with domestic workers’ rights and decent work standards.

Which of the statements given above is/are correct?

(a) 1 only (b) 2 only (c) Both 1 and 2 (d) Neither 1 nor 2

Answer: (c)

One-line wrap

Make homes fair workplaces—choose law, dignity and portability for India’s domestic workers.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

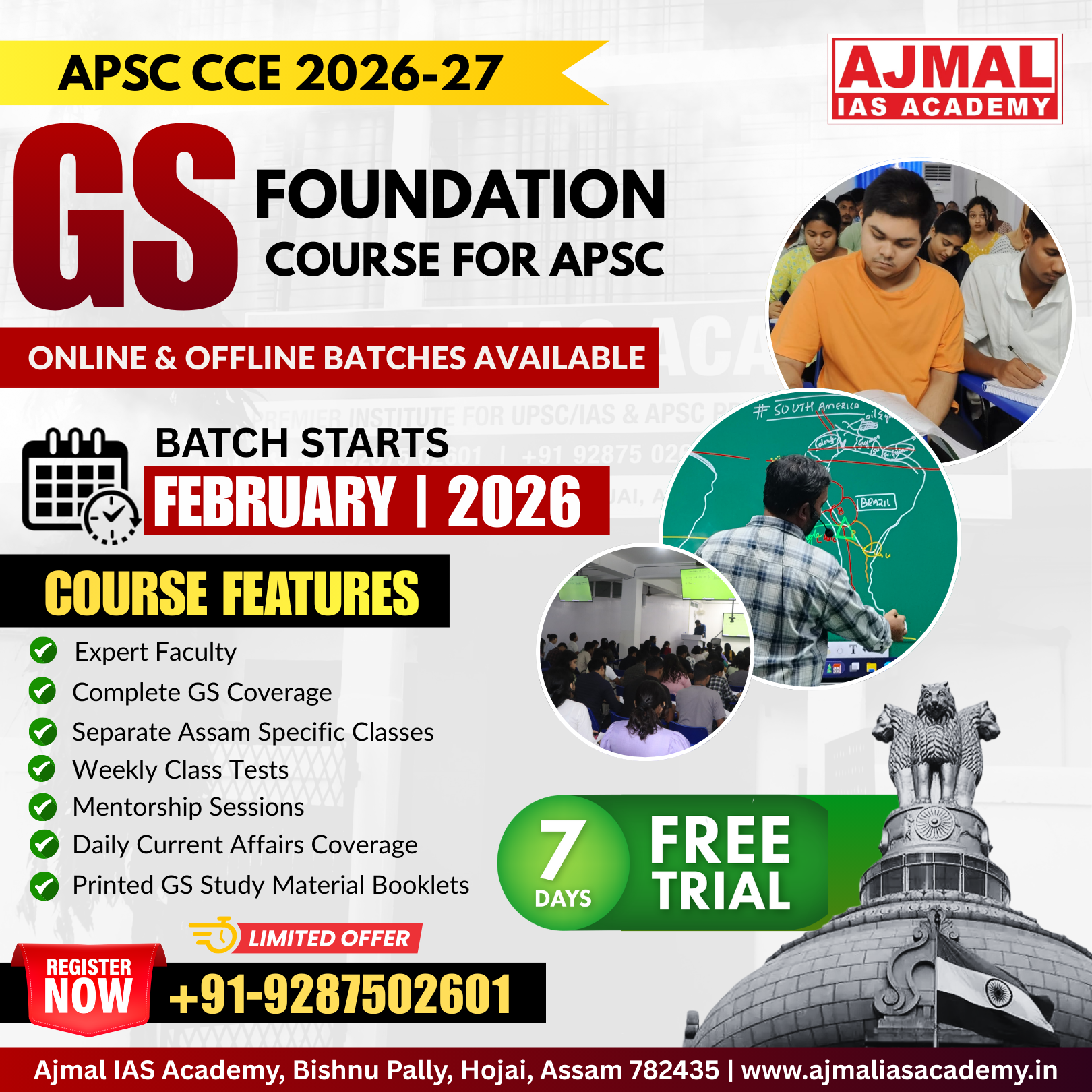

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.