Polity, Governance, Ethics, Media and Communication, Current Affairs, and Cybersecurity.

What is the news and the core issue

Nepal imposed a blanket ban on twenty-six social media platforms in early September 2025, saying many had not registered locally and were spreading harmful content. The ban triggered youth-led protests, reported deaths, and the resignation of the Prime Minister; an interim government later lifted the ban. Through the crisis, major platforms were mostly passive: short statements or silence, quick compliance with block orders, and no strong technical workarounds or legal pushback. The episode highlights a wider South Asian pattern: during unrest, platforms often prioritise market access and regulatory safety over users’ digital rights and free speech, unless courts or public pressure force change.

Recent occurrences, beyond Nepal

- Pakistan has repeatedly restricted major platforms during political tensions.

- India has seen frequent targeted shutdowns in recent years. The Supreme Court’s judgment in Anuradha Bhasin set due-process limits, but compliance remains uneven. Platforms usually restrict content within the country or take down posts when ordered.

- When platforms do challenge orders, results vary. The platform now called X (earlier Twitter) lost a prominent case in the Karnataka High Court, while the traceability challenge by WhatsApp is still pending. Overall, litigation is rare and slow, so companies mostly comply first.

The Nepal case — what happened and how social media shaped it

What the government did: Issued a blanket block on Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, X, and others for not meeting new registration and local-presence rules, and cited concerns about fake accounts and crime.

How citizens responded: Youth groups shifted to other channels (platforms that had registered, text messages, and virtual private networks) to organise. Videos and cost-of-living narratives spread quickly before and despite the ban, fuelling mobilisation and public anger over police firing. Under heavy pressure, the government lifted the ban.

What platforms did:

- Most accepted the blocks, issued safety notes, and did not roll out strong country-specific workarounds (for example, no emergency text-message bridges or rapid alternative domains).

- They did not file urgent legal challenges in Nepal during the peak of unrest.

- The approach signalled a familiar risk calculus: avoid confrontation in a small market; protect staff and licences; hope the storm passes.

How platforms typically behave in crises

When governments order takedowns or shutdowns during unrest, big platforms tend to comply quickly, minimise public friction, and limit technical workarounds. Three reasons recur: legal exposure under local laws, business incentives (advertising, growth, licences), and safety of local employees.

- Compliance over contest: Restricting content inside the country and account takedowns are faster than court fights. Only in exceptional cases do platforms sue, and success is uncertain.

- Limited technical help: Unlike some secure-messaging tools that enable proxies or domain fronting, mainstream platforms rarely push such tools in a single-country crisis to avoid being seen as evading sovereign orders.

- Transparency, but after the fact: Companies publish transparency reports on takedown and data-request volumes, but these arrive months later, offering little real-time relief to users.

Why this matters for rights

- Scale of shutdowns is rising: The world has recorded a high number of internet disruptions linked to protests and elections.

- Courts and rules exist, but gaps remain: Even where courts demand necessity and proportionality (as in India), loopholes in telecommunications suspension rules or weak oversight can prolong curbs.

- Global standards are clear: Guidance from the United Nations urges firms to conduct human-rights due diligence, resist overbroad orders, and protect expression and privacy. Practice still lags principle.

The way ahead —

A) Government

- Follow constitutional tests: Any restriction should be lawful, necessary, proportionate, time-bound, and published with reasons. Reviews should be independent, not only executive.

- Use narrow tools first: Prefer content-level remedies over blanket platform or internet bans; avoid long, rolling shutdowns.

- Independent appeals: Create a fast appeal mechanism for platforms and users to contest overbroad orders.

B) Social media platforms

- Crisis playbook: Publish a country-specific human-rights response plan stating when they will notify users, seek court review, or narrowly restrict content instead of total takedowns.

- Minimal viable access: Where lawful and safe, enable low-bandwidth mirrors, fallback domains, or proxy support for verified civic information such as election commissions and emergency services.

- Faster transparency: Release a near real-time ledger during crises (order received, scope, whether an appeal was filed), not only quarterly reports.

- Local risk without capture: Maintain small compliance teams but keep content policy and legal decisions insulated from political pressure.

C) Civil society and media

- Evidence and litigation: Track every order; file Right to Information requests; move courts for publication of blocking and suspension orders.

- User safety: Spread digital-hygiene guides (verification, backups, safer circumvention).

- Coalitions: Build national and regional alliances so cases in one country can draw support and precedents from others.

Exam hook

Key takeaways

- During unrest, platforms usually comply first and challenge later, if at all. Legal risk, business incentives, and staff safety drive this choice.

- Blanket bans escalate conflict and harm the economy, education, and public safety; they are rarely necessary or proportionate.

- Courts can help only if orders are public and reviewable: blocking and suspension directives should be reasoned, time-bound, and open to appeal.

- Best practice exists in international standards, but implementation is weak.

- Nepal’s crisis shows the cost of fast bans and slow platform responses: anger surged, and policy collapsed.

Mains practice question

In periods of political unrest, social media companies often stay silent or comply with government orders rather than defend digital rights. Critically analyse this conduct. Propose a rights-respecting framework for governments and platforms.

One-line wrap

Do not switch off the public square—use narrow, lawful, time-bound measures, and make platforms show their rights playbook in real time.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

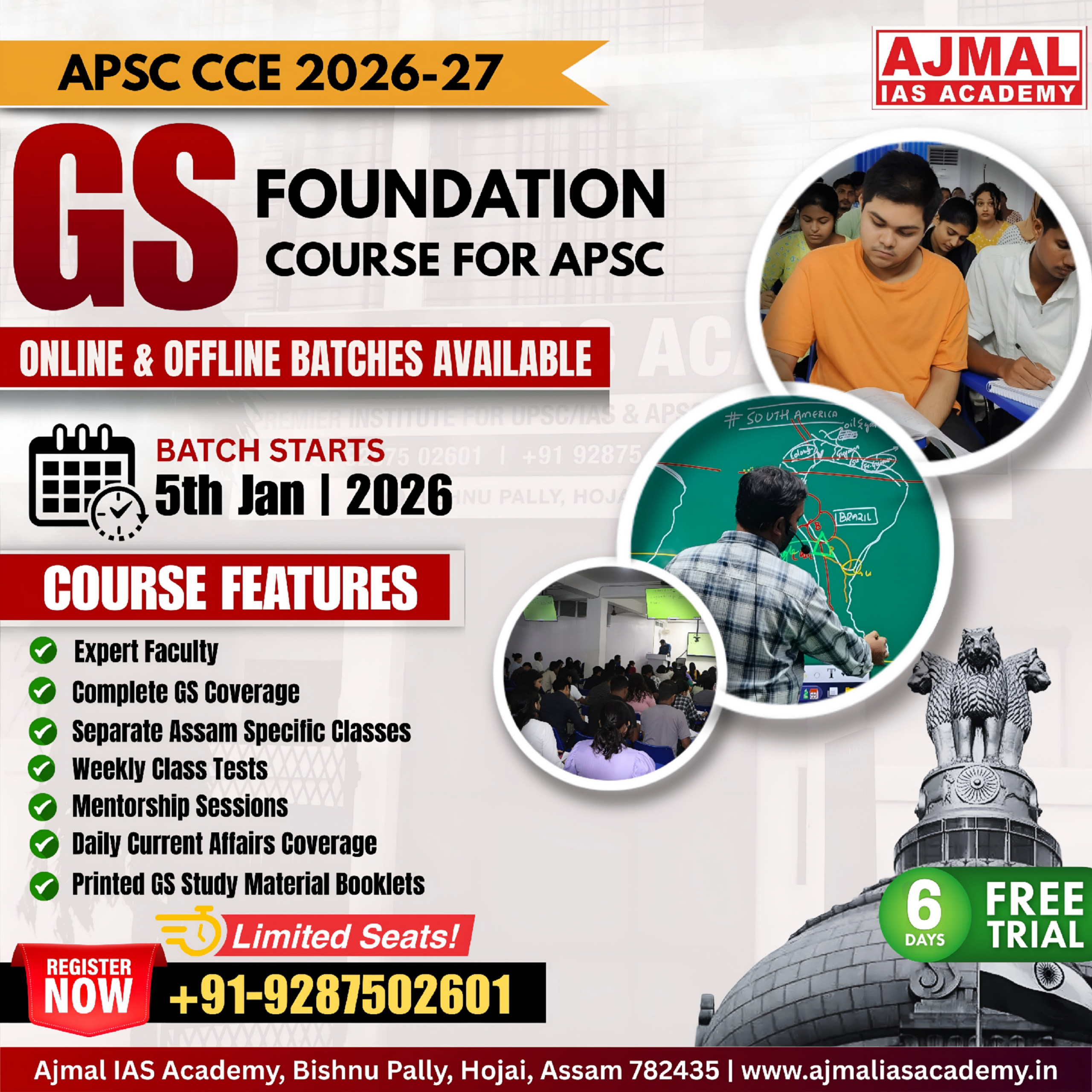

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.