Syllabus: GS-I: Modern Indian History (Colonial expansion in Northeast India)

Why in the News?

The Treaty of Yandabo, signed on February 24, 1826, ended the First Anglo–Burmese War (1824–1826) and marked a turning point not only in the history of Assam but also in the broader political geography of Northeast India.

While the treaty formally transferred control of Assam from Burmese occupation to the British East India Company, its deeper consequence was the institutionalisation of colonial governance, racial classification, and territorial restructuring that transformed Assam’s socio-economic and cultural fabric.

This was not merely a military outcome but a civilisational shift—from a precolonial polity grounded in fluid frontiers and cultural coexistence to a colonial state defined by boundaries, categories, and control.

Assam before the Treaty of Yandabo

Before 1826, Assam under the Ahom dynasty (1228–1826) had developed a distinctive political and cultural identity rooted in the integration of hill and plain societies, and in administrative practices such as the paik system, which balanced state control with community autonomy.

However, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw political instability within the Ahom kingdom, culminating in internal conflict and Burmese intervention. The Burmese invasion (1817–1824) devastated the valley, displacing thousands and collapsing the old order. When the British defeated Burma, Assam was annexed as part of the peace settlement, symbolising the first formal step in British expansion into Northeast India.

Colonial Reordering after 1826

The British did not view Assam as a coherent socio-political region but as an extension of the Bengal Presidency—a resource frontier to be surveyed, categorised, and exploited.

The colonial administration deployed three key instruments to establish control:

- Census and Cartography: The systematic mapping and enumeration of the population created new administrative and ethnic boundaries.

- Communities that had once shared fluid cultural ties were reclassified into rigid categories—“hill” vs “plain,” “tribal” vs “non-tribal,” “indigenous” vs “immigrant.”

- Anthropological and Ethnographic Knowledge: Scholars like Dalton, Risley, and others produced racial hierarchies and typologies that influenced land rights, political representation, and social mobility.

- This “ethnographic state” legitimised control through knowledge.

- Administrative and Legal Frameworks: Laws like the Inner Line Regulation (1873), Scheduled Districts Act (1874), and Frontier Tracts Regulation (1880s) institutionalised separation between hill and plain areas.

- These “protective” laws were in reality instruments of strategic governance, designed to control mobility, prevent political unity, and secure the frontier against other imperial powers.

- These “protective” laws were in reality instruments of strategic governance, designed to control mobility, prevent political unity, and secure the frontier against other imperial powers.

Economic Transformation

The discovery of indigenous tea plants in the early 1830s transformed Assam’s economy and ecology. The British declared vast areas of forest and common land as “wastelands” and converted them into plantations, initiating the Assam Tea Industry—a symbol of empire and exploitation.

- Plantation Labour: To meet labour demands, the British imported workers from Central India (Chotanagpur, Santhal Parganas, Bihar) under the Indenture System.

- This migration permanently altered Assam’s demographic composition, creating a distinct tea garden community that remains socially and economically marginalised even today.

- Extractive Economy: The colonial economy in Assam was designed for resource extraction, not regional development—tea, oil (discovered in Digboi, 1889), coal, and timber were exported, while local populations saw little infrastructural or social benefit.

- Land Displacement: Traditional landholding patterns were replaced by private property and plantation leases.

- Indigenous peasants, especially in the Brahmaputra Valley, were dispossessed, sowing the seeds of agrarian distress and identity politics that persist.

- Indigenous peasants, especially in the Brahmaputra Valley, were dispossessed, sowing the seeds of agrarian distress and identity politics that persist.

Constructing Identities and Faultlines

Colonialism did not merely redraw territorial boundaries—it manufactured social hierarchies.

The categorisation of communities—Ahoms as “non-tribal,” Nagas and Khasis as “tribal,” Bengalis as “immigrants”—became the grammar of governance.

These distinctions institutionalised ethnic consciousness, later transforming into political faultlines.

- Bernard Cohn’s Observation (1966):

Colonialism was a “cultural project of rule,” where control was exercised through knowledge, classification, and bureaucratic inscription.

In Assam, these classifications shaped:

- Electoral representation and land ownership in the colonial and post-colonial era.

- Identity-based movements such as the Assam Agitation (1979–1985) and Bodo movement.

- The persistent tension between indigeneity and migration, amplified by policies like NRC and CAA.

From Colonial Control to Post-Colonial Integration

1. Constitutional Safeguards and Institutional Responses

After independence, India sought to heal these fractures through institutional innovations:

- Bordoloi Committee (1948): Recommended Autonomous District Councils under the Sixth Schedule to safeguard tribal interests and decentralise governance.

- North Eastern Council (NEC, 1971): Created for regional planning and coordination.

- Ministry of Development of North Eastern Region (DONER, 2001): Institutionalised the federal commitment to development and connectivity.

2. Ethnic Mobilisations and Political Settlements

- Assam Accord (1985): Addressed migration and citizenship, promising protection of Assamese identity.

- Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC, 2003): Formed after decades of ethnic mobilisation and insurgency, symbolising the balance between autonomy and integration.

Yet, these measures did not fully resolve the deep-seated identity anxieties inherited from the colonial past.

The NRC update (2019) and CAA (2019) reignited debates on belonging, ethnicity, and citizenship—demonstrating that colonial-era boundaries of inclusion and exclusion still shape Assam’s politics.

Contemporary Relevance: The Development–Identity Paradox

In the 21st century, Assam stands at a developmental crossroads. Mega infrastructure projects, industrial corridors, and connectivity initiatives under the Act East Policy project new economic opportunities. Yet, these carry the risk of reproducing extractive models reminiscent of colonial development.

Two persistent deficits define the region:

- Democratic Deficit – Uneven representation and weak local governance in hill and border areas.

- Development Deficit – Growth that often ignores ecological sensitivity, cultural diversity, and community participation.

Balancing economic integration with cultural preservation and ecological resilience remains Assam’s foremost challenge.

Way Forward

- Decolonising Development: Development models must reflect local ecological and cultural realities rather than externally imposed growth paradigms.

- Participatory Governance: Strengthen institutions like Autonomous Councils and Panchayati Raj bodies to ensure inclusive decision-making.

- Revisiting Historical Injustices: Recognise the contribution and marginalisation of tea garden workers, migrant peasants, and tribal groups in state narratives.

- Reconciliation of Identities: Promote inclusive citizenship that transcends colonial binaries of “insider” and “outsider.”

- Sustainable Integration: The Act East Policy should not merely aim at economic corridors but also at cultural and environmental cooperation with Southeast Asia.

Conclusion

The Treaty of Yandabo (1826) was not just an end to war—it was the beginning of colonial modernity in Assam, which reshaped its geography, economy, and identity.

From tea plantations to territorial lines, the British cultivated not only commerce but also categories that continue to influence contemporary politics and development.

Today, as Assam redefines its place in a rapidly transforming India and Indo-Pacific region, the challenge is to move beyond colonial legacies of extraction and exclusion towards a model of inclusive growth, participatory democracy, and ecological balance.

Only by addressing these historical continuities can Assam—and by extension, Northeast India—realise its true potential as a region of diversity, resilience, and connected futures.

Treaty of Yandabo (1826)

Main Conditions:

|

Mains Practice Question

“The Treaty of Yandabo (1826) marked not just the beginning of British rule in Assam but also the origin of its modern political and identity faultlines.” Discuss how colonial policies reshaped Assam’s social and economic structure, and assess the post-independence attempts to reconcile these divisions.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

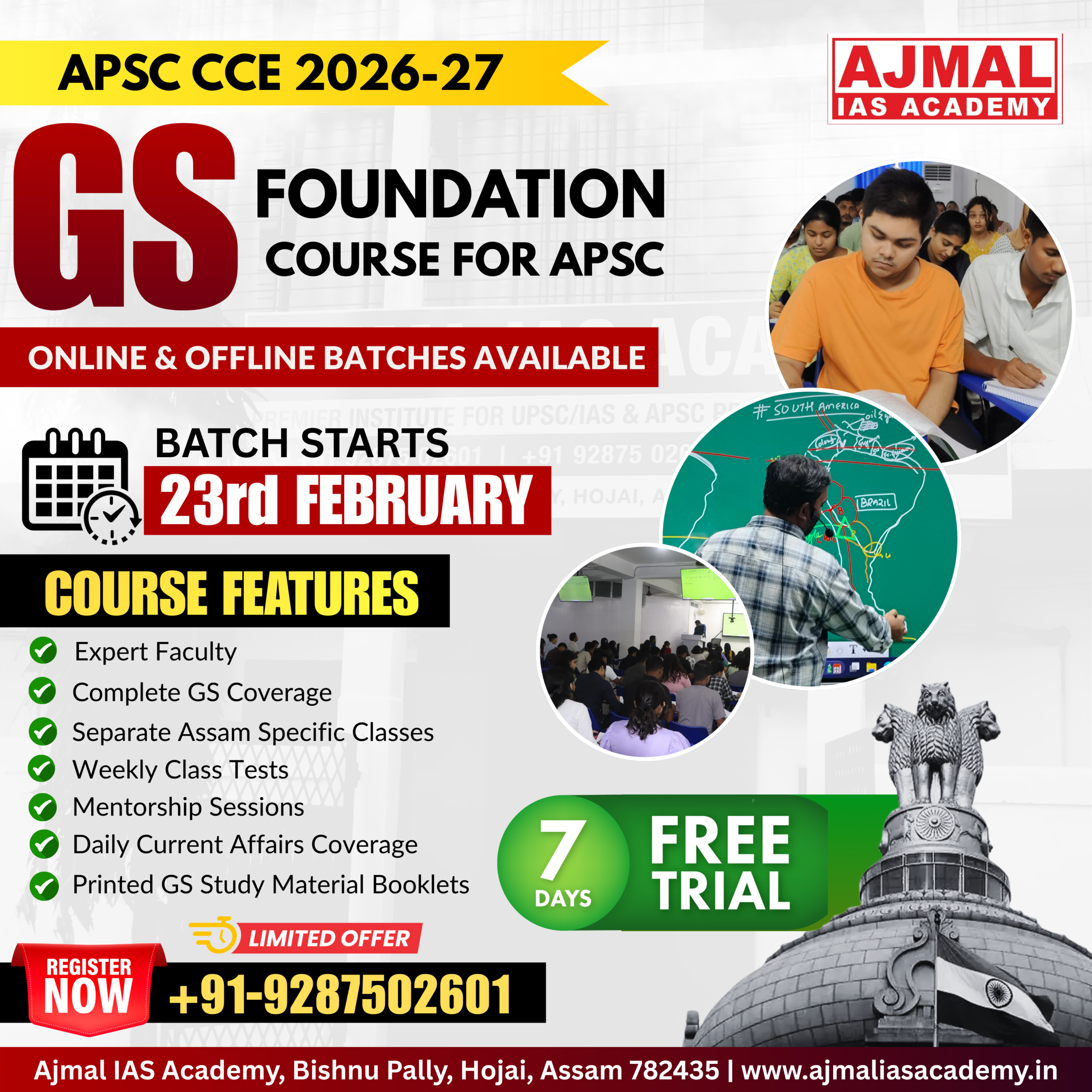

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.