Relevance: GS Paper II (Polity, Governance, Rights) | Source: The Hindu

Context: The Conflict of Rights

A three-judge Bench of the Supreme Court, led by CJI Surya Kant, has agreed to examine a critical constitutional question: Does the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023 kill the Right to Information (RTI) Act?

Petitioners argue that the new data law uses the “shield” of Privacy to effectively cripple the citizen’s Right to Know, creating a veil of secrecy around public officials.

1. The Core Battle: Section 44(3) vs. Section 8(1)(j)

The controversy centers on how the new DPDP Act changes the rules for denying information.

| Feature | Before DPDP Act (Old Regime) | After DPDP Act (New Regime) |

| The Rule | Section 8(1)(j) of RTI exempted personal info ONLY IF it had no relation to public activity or invaded privacy. | Section 44(3) of DPDP removes all qualifiers. It creates a Blanket Ban on disclosing “information which relates to personal information.” |

| Public Interest Test | Allowed: A Public Information Officer (PIO) could disclose private info if the “larger public interest” justified it. | Removed: There is no “Public Interest Test.” If data is “personal,” it is denied, regardless of public good. |

| The Logic | Chisel approach: Carefully carving out exceptions. | Hammer approach: Smashing the right to know completely. |

2. Why is this a “Body Blow”?

- The “Hammer” Argument: Advocates argued in court that instead of using a “chisel” to fine-tune privacy, the government used a “hammer” to smash transparency.

- Unguided Discretion: The new law gives officials “absolute power” to reject RTI applications. The term “personal information” is vague and can be used to hide corruption—like an official’s assets or a defaulting businessman’s loan details.

- State vs. Individual: The Right to Privacy is meant to protect the individual from the State. Ironically, this Act allows the State to use privacy to hide from the citizens.

3. Real-World Impact

The removal of the “Public Interest Test” has severe implications for daily governance:

- Social Audits: If you ask for a list of PM-AWAS Yojana beneficiaries to check for fake names, it can now be denied as “personal information” of the beneficiaries.

- Accountability: If an activist seeks the educational degree of a Minister or the asset declaration of a bureaucrat to verify authenticity, it can be rejected outright.

4. Way Forward

To resolve this “Privacy vs. Transparency” deadlock, a balanced approach is needed:

- Harmonious Construction: The Supreme Court must “iron out the creases” (as noted by the CJI) to ensure Privacy doesn’t swallow Transparency. Both rights must co-exist.

- Define “Personal Information”: The law needs a stricter definition of “personal data.” Information about a public servant’s official conduct (e.g., usage of funds, appointments) should NOT be hidden under the guise of “personal info.”

- Revive Section 8(2): The Judiciary can clarify that Section 8(2) of the RTI Act (which allows disclosure if public interest outweighs harm) still overrides the new exemption. This would act as a critical “safety valve” for accountability.

UPSC Value Box

Constitutional Concept:

- Hierarchy of Rights:

- Right to Information: Derived from Article 19(1)(a) (Freedom of Speech).

- Right to Privacy: Derived from Article 21 (Right to Life – Puttaswamy Case).

- The Challenge: In a democracy, neither right is absolute. The Supreme Court must now decide if Privacy can be used to defeat Transparency, or if a “Harmonious Construction” (balance) is needed.

Summary

The Supreme Court is set to review whether the DPDP Act, 2023 unconstitutionally restricts the RTI Act. By removing the “Public Interest Test,” the new law potentially allows corrupt officials to hide behind the veil of “personal privacy,” fundamentally altering the transparency landscape of India.

One Line Wrap: Privacy should be a shield for the citizen, not a veil for the State.

Q. “The Right to Information and the Right to Privacy are often seen as competing rights. Critically analyze how the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, alters the balance between transparency and privacy in India’s governance framework.” (10 Marks, 150 Words)

Model Hints

- Introduction: Mention the conflict between Article 19(1)(a) (RTI) and Article 21 (Privacy).

- Body:

- The Shift: Explain the amendment to Section 8(1)(j)—from “Qualified Exemption” to “Total Exemption.”

- The Loss: Highlight the removal of the “Public Interest Test.”

- The Impact: Discuss how this hinders accountability (e.g., hiding assets of public servants, beneficiaries of schemes).

- Conclusion: Conclude that while privacy is essential, a transparent democracy requires a “Public Interest Override” to prevent secrecy from breeding corruption.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

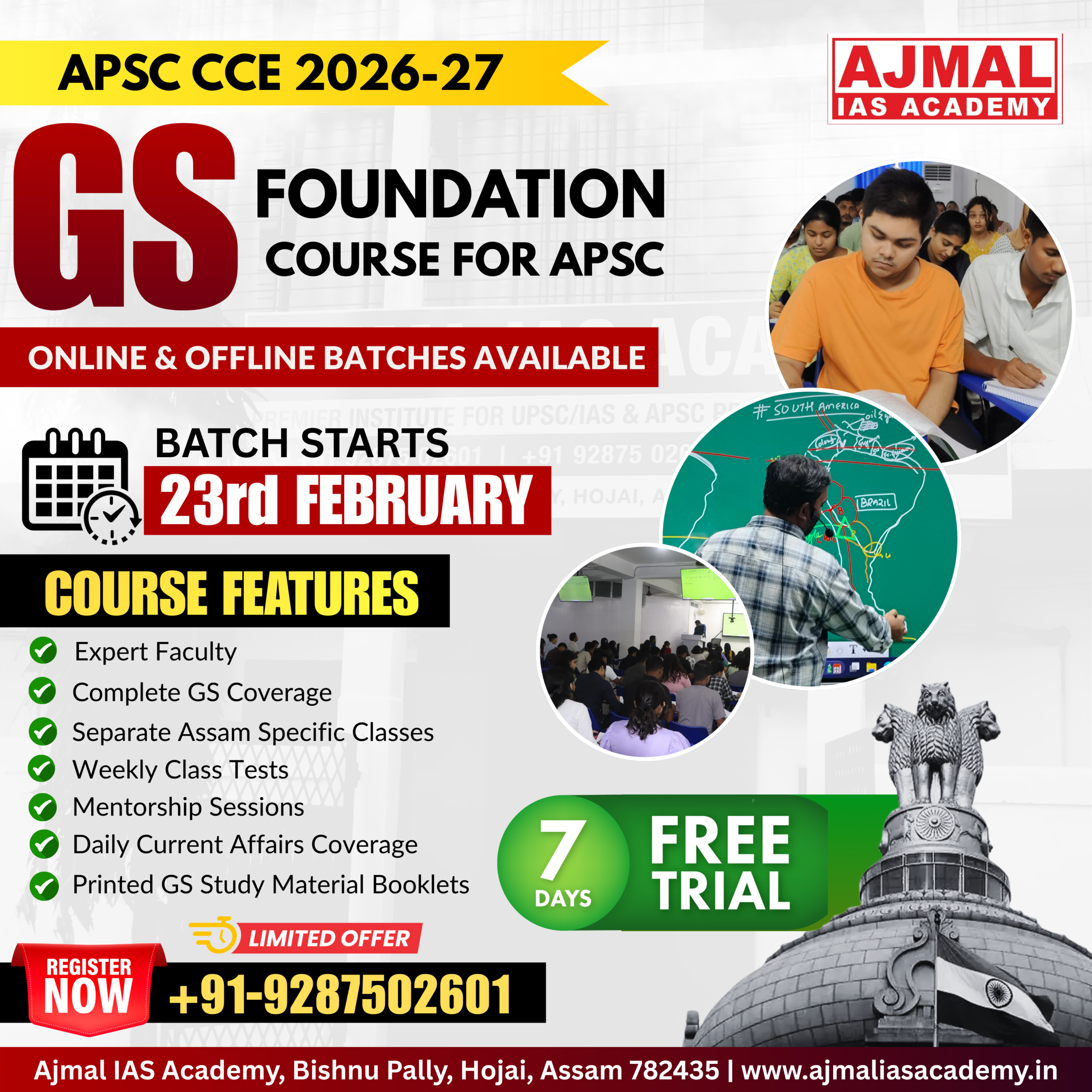

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.