Q.1 Discuss the salient features of Harappan architecture. (Answer in 150 words)

Introduction

The Harappans (2600–1900 BCE) created one of the world’s earliest planned urban societies. Their towns were not random settlements but carefully designed to function like a well-managed civic system.

Core Features

- Urban Layout:

Cities followed a grid pattern with straight streets, fixed widths, and division between citadel (public/administrative area) and lower town (residential area). Fortified walls ensured safety. - Sanitation & Water:

Almost every house had bathrooms and latrines connected to covered brick drains. There were inspection holes for cleaning. At Dholavira, huge stone reservoirs stored water in an arid zone. - Building Materials:

They used baked bricks of standard 1:2:4 ratio. Weights and measures were uniform, showing coordination across the region. - Public Buildings:

- The Great Bath (Mohenjo-daro): watertight pool, probably for ritual bathing.

- Granaries (Harappa): storage for surplus grain.

- Dockyard (Lothal): a brick basin showing knowledge of maritime trade.

- Large Pillared Hall( Assembly Hall) at Mohanjodaro

- Urban Layout:

- Houses:

- Mostly courtyard style with rooms around open space, stairs to upper floors. Focus was on functionality and privacy, not palaces or temples.

- Houses of varying size, indicating social differentiations.

Analysis

- The Harappan city valued cleanliness, order, and public welfare, rather than showing off royal power.

- Absence of palaces/temples suggests collective civic spirit over dynastic rule.

Modern Relevance

- Water-sensitive design: Dholavira reservoirs inspire today’s rainwater harvesting.

- Building standards: Brick ratios remind us of modern building codes.

- Public health: Connected drains resemble Swachh Bharat Mission sanitation models.

- Risk awareness: Cities shifted with river changes—lessons for climate adaptation and urban hazard mapping today.

Conclusion

The Harappan city was not just built, it was managed through design. Its lessons in sanitation, water management, standardisation, and risk planning remain strikingly relevant for India’s urban future.

Q.2 Examine the main aspects of Akbar’s religious syncretism. (Answer in 150 words)

Introduction

Akbar (1542–1605) reshaped sovereignty through sulh-i-kul (universal peace)—an ethic of governance prioritising order, justice, and inclusivity over sectarian privilege. His syncretism was less theology, more statecraft to stabilise a diverse empire.

Instruments & Practices

- State Toleration: Abolished pilgrimage tax (1563) and jizya (1564); gave high offices to Rajputs and non-Muslims; practiced legal pluralism. Akbar issued decrees prohibiting forced religious conversions of non-Muslims living in the empire.

- Ibadat Khana (1575): Platform for interfaith debates—Muslim ulema, Brahmins, Jains, Zoroastrians, Jesuit priests—encouraging dialogue.

- Mahzar Nama (1579): Declared emperor as final arbiter in interpreting religious law, introducing reason into policy-making.

- Din-i-Ilahi (1582): A small ethical fellowship promoting piety, loyalty, restraint, and harmony—drawing on Sufi devotion, Jain ahimsa, and Zoroastrian practices.

- Translation Bureau (Maktab Khana): Rendered Sanskrit works into Persian (Razmnama, Mahabharata), creating a shared intellectual culture.

- Social Reforms: Discouraged child marriage, sati, and wasteful consumption; ethics blended into policy.

Assessment

- Syncretism was practical governance, not merging religions.

- It nurtured composite culture, gave legitimacy through fairness, and reduced sectarian conflict.

- Limitations: Elite-centric outreach, limited rural impact, and later reversals (e.g., Aurangzeb’s reimposition of jizya).

Contemporary Significance (hidden demand)

- Norm-setting: Anticipates modern ideals of equality, fraternity, and interfaith dialogue.

- Policy lessons: The Mahzar Nama foreshadows reason-guided arbitration in plural societies.

- Soft power: His court culture (art, language, architecture) showed how culture itself can be a tool of good governance.

Conclusion

Akbar’s syncretism survives less as a religious doctrine and more as a governance ethic—where tolerance was operationalised, culture mobilised, and reason institutionalised. It remains a model for managing diverse societies today.

Q. 3 “The sculptors filled the Chandella art form with resilient vigor and breadth of life.” Elucidate. (Answer in 150 words)

Introduction

The Chandellas (10th–12th century) at Khajuraho created temples where architecture and sculpture blended seamlessly, producing a form of visual poetry that embodied both devotion and daily life.

How Vigor & Breadth Are Achieved

- Formal Dynamism:

- Figures are carved deeply, making them look lively.

- S-curves and tribhaṅga (three-bend pose) give bodies a sense of movement.

- Rows of sculptures rise with the temple tower (nagara śikhara), creating upward rhythm.

- Thematic Plurality:

- Depicts gods, goddesses, surasundarīs (graceful women), mithunas (couples), dancers, musicians, warriors, artisans, animals, and royal life.

- Sacred and secular scenes sit side by side—making the temple a miniature universe of society.

- Rasa & Technique:

- Fine sandstone carving, detailed jewelry/drapery, expressive faces bring out śṛṅgāra (love), vīra (heroism), and adbhuta (wonder).

- Iconographic programs connect daily scenes to larger metaphysical ideas.

- Symbolic Depth:

- Erotic imagery is symbolic of fertility, cosmic union, and spiritual ascent in tantric–bhakti traditions.

Critical Notes

- Temples were not mere decoration; sculptures worked as picture-books of values and faith for a largely non-literate society.

- Patronage showed political legitimacy—rulers displayed prosperity, while artisans reached peak craftsmanship.

Modern Relevance (hidden demand)

- Heritage & Identity: UNESCO-listed Khajuraho supports cultural diplomacy, tourism, and local livelihoods, but also needs sensitive conservation.

- Aesthetic Literacy: Counters simplistic views of erotic art; adds to debates on body, gender, and sacredness.

- Craft Revival: Provides design vocabularies for stonework, useful in architecture schools and heritage conservation.

- Plural Ethos: Temples embody an inclusive vision where worship, love, and daily life are part of a continuum.

Conclusion

Khajuraho reflects creative energy disciplined by form—a living record of technique, faith, and society. Its enduring value lies not only in spirituality but also in education, cultural identity, and tourism-based economy, making it a treasure of both past and present India.

Q.11 Mahatma Jotirao Phule’s writings and social reform efforts touched issues of almost all subaltern classes. Discuss. (Answer in 250 words)

Introduction

Mahatma Jotirao Phule (1827–1890) fought caste hierarchy and brahmanical patriarchy together, highlighting how they oppressed Shudras–Atishudras, women, widows, peasants, and “untouchables.” Through schools, writings, and social organisations, he gave concrete remedies for different oppressed groups.

Who He Addressed & How

- Girls & Women

- With Savitribai Phule and Fatima Sheikh, started India’s first girls’ school (Pune, 1848).

- Opened Balhatya-Pratibandhak Griha to prevent female infanticide.

- Supported widow remarriage and safer childbirth.

- “Untouchables” (Atishudras)

- Opened his own well (1868) to communities denied access to water.

- In Gulamgiri (1873), compared caste to slavery and demanded education, dignity, and civic rights.

- Sarvajanik Satyadharma Pustak

- Shudra Cultivators & Rural Poor

- In Shetkaryacha Asud (1881), exposed landlord–moneylender exploitation, linking caste oppression with rural poverty.

- All Non-elite Believers

- Founded Satyashodhak Samaj (1873) to promote priest-free marriages, vernacular debates, and equality in rituals.

- Mass Education & Awareness

- Through plays like Tritiya Ratna (1855) and pamphlets in Marathi, he reached illiterate audiences, exposing ritual exploitation.

Why It Touched Almost All Subalterns

Phule treated caste, gender, and class oppression as interconnected. His solutions—education, property rights, civic dignity, and equal rituals—created a comprehensive program of emancipation.

Contemporary Relevance

His vision echoes today in:

- Affirmative action and reservations for social justice.

- Universal schooling drives and gender education.

- Anti-atrocity laws protecting Dalits.

- Women’s empowerment movements.

- Secular civil marriage systems that bypass priestly monopoly.

Conclusion

Phule converted dissent into institutions—schools, wells, shelters, Samaj—that embodied equality in daily life. His efforts turned ordinary spaces into sites of liberation for India’s marginalised, a legacy still shaping social justice today.

Q.12 Trace India’s consolidation process during the early phase of independence in terms of polity, economy, education, and international relations. (Answer in 250 words)

India’s Early Consolidation (1947–1960s)

Introduction

When India became independent, it faced partition violence, millions of refugees, princely states, food shortages, and deep poverty. Yet, in the first 15 years, India managed to build a stable democracy, start economic planning, expand education and science, and carve an independent role in world politics.

Polity

- Constitution (1950): Gave universal adult franchise from the start, guaranteeing Fundamental Rights, Directive Principles, and independent institutions like the Election Commission, Supreme Court, CAG.

- Territorial integration: Patel and Menon brought 560+ princely states into the Union; the States Reorganisation Act (1956) created linguistic states while keeping unity.

- Democracy in practice: Peaceful elections in 1952, 1957, and 1962 built trust; Panchayati Raj was initiated after the Balwantrai Mehta report (1957).

Economy

- Planned mixed economy: Creation of Planning Commission (1950); Five-Year Plans focused on agriculture (I), heavy industry (II), and self-reliance (III).

- Infrastructure & PSUs: Dams like Bhakra–Nangal, Hirakud, DVC; SBI (1955) for rural credit; investment in atomic energy (1948) and research labs (CSIR).

- Land reforms: Zamindari abolition and tenancy laws tried to make agriculture fairer, though success was uneven.

Education & Science

- Commissions: Radhakrishnan (1948–49), Mudaliar (1952–53).

- Institutions: UGC (1956); IITs (Kharagpur 1951, others by 1961); AIIMS (1956); NCERT (1961)—laying the base for science-led nation building.

International Relations

- Non-Alignment: India became a leader at Bandung (1955) and Belgrade (1961); framed Panchsheel (1954) with China.

- Decolonisation: Supported Asian–African countries and UN peacekeeping.

- Conflict management: Dealt with Kashmir war (1947–48); signed Indus Waters Treaty (1960); integrated Goa (1961)—showing a balance of assertiveness and legality.

Challenges (hidden demand)

- Food shortages and reliance on PL-480 US grain imports.

- Uneven land reforms—many small tenants excluded.

- Linguistic reorganisation created unity but also fuelled regional politics.

- Defence weakness was exposed in the 1962 war with China.

Conclusion

By creating strong institutions, investing in dams, industries, IITs, and securing independent foreign policy, India turned a fragile postcolonial state into a durable democracy. Its model of democracy + planning + science + non-alignment still shapes India’s path today.

Q.13 The French Revolution has enduring relevance to the contemporary world. Explain. (Answer in 250 words)

Introduction

The French Revolution (1789–99) reshaped politics by introducing popular sovereignty, rights-based citizenship, equality before law, secular authority, and centralized administration. Its core ideas still form the foundation of modern democracies.

Enduring Elements & Contemporary Salience

- Rights & constitutionalism: The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen inspired the UDHR, civil rights movements, constitutional courts, and campaigns like #MeToo.

- Citizen–nation & fraternity: Defined belonging through citizenship, not lineage. Fraternity built the basis of social solidarity and anti-discrimination laws.

- Legal–administrative reforms: The Napoleonic Code, merit-based bureaucracy, and standardized administration shaped many civil-law systems in Europe, Latin America, and Africa.

- Mass politics: The left–right political spectrum, petitions, strikes, referendums, and national symbols (tricolour, Marseillaise) remain global repertoires of protest and democracy.

- Secular citizenship: The French model of laïcité still drives debates on religion–state relations (e.g., veil/hijab controversies).

- Socio-economic reforms: Price controls, progressive taxation, and peasant emancipation were early steps toward the welfare state and land reforms.

Cautions (Hidden Demand)

- The Terror shows the dangers of suspending liberty in the name of virtue.

- Exclusions: Women (Olympe de Gouges) and colonies (till the Haitian Revolution, 1804) highlight the gap between rhetoric and reality—relevant for intersectional rights today.

- Exported freedom: Military campaigns often turned into domination, a warning for modern interventions abroad.

Diffusion & India Link

- Global echoes: Metric system, civil codes in Quebec and Egypt, universal conscription (levée en masse).

- India: The Preamble’s “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” directly echoes the French motto; Constituent Assembly debates borrowed from French liberal traditions while adapting them to India’s plural society.

Conclusion

The French Revolution’s legacy is normative (rights), institutional (codes/administration), and pedagogic (mass politics). It continues to empower democracies to expand freedom and equality, while warning against illiberal excess in the name of the people.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

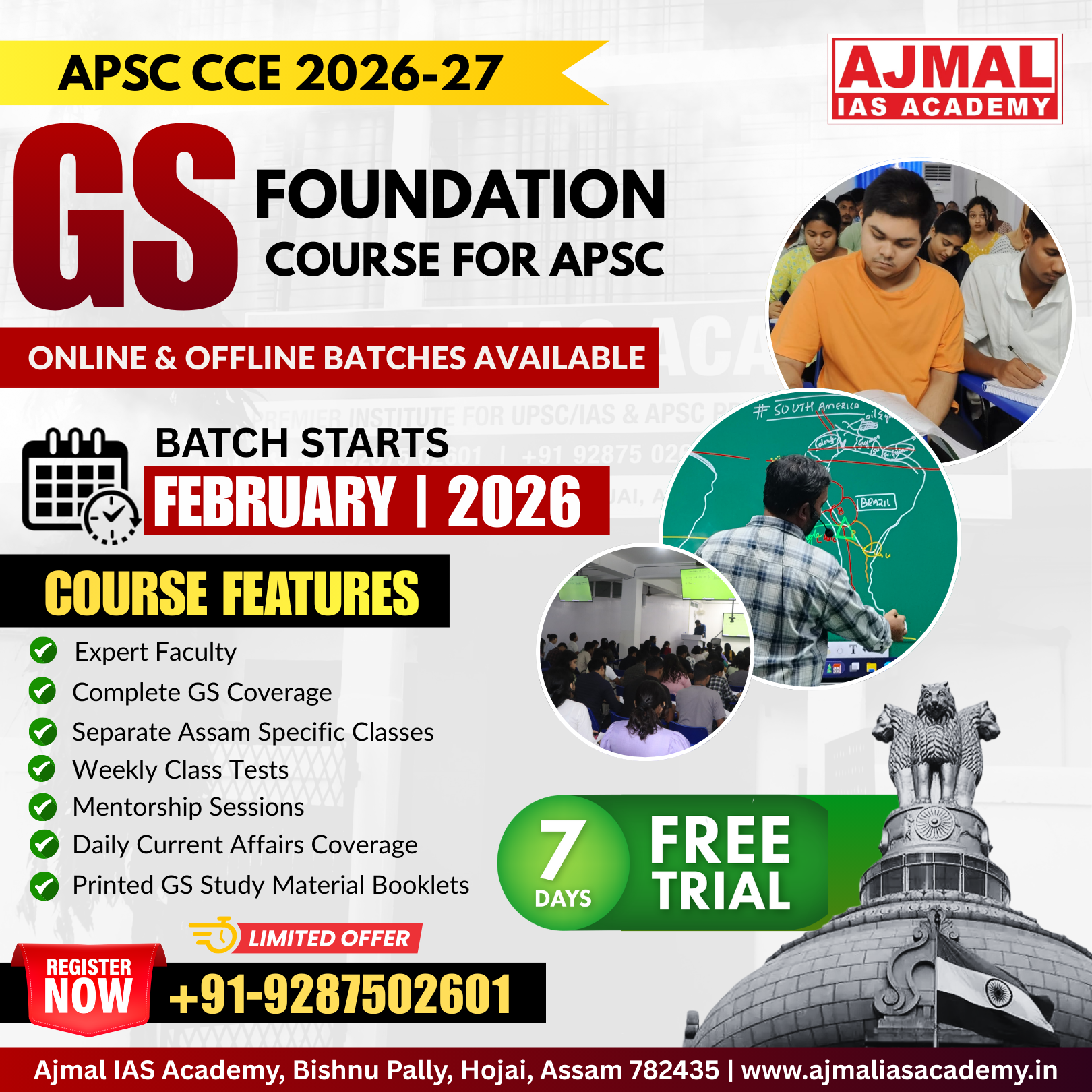

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.