Economy, Agriculture, Governance, Social Issues, Government Policies, and Current Affairs.

Farmers in the Nashik belt and nearby districts are selling onions below cost because of a glut, damage to stored bulbs, uncertain export rules, and the way public buffer stocks have been released. They want quick relief, steady export policy, and smarter use of buffer stocks so prices do not crash further in the very markets where they sell.

What is happening on the ground—and why prices collapsed

The price gap. Many farmers say they are getting roughly eight hundred to one thousand rupees for a quintal of ordinary onions, while the all-in cost of growing, curing, storing, and transporting a quintal is commonly placed between two thousand two hundred and two thousand five hundred rupees. That gap is the core pain.

Why the gap opened this year

- Bigger harvest and weak demand at the same time. Maharashtra grew more onions than the nearby markets could absorb in this window.

- Quality loss in storage. Rabi onions, harvested in March–May, are meant to carry the country through the rest of the year. Farmers store them for months to sell when prices are better. Unseasonal rain and humidity damaged many stocks in storage towns, so buyers cut rates for everyone.

- Public buffer stock in the same cities. The Union government buys onions to build a buffer under the price stabilisation fund and sells them in cities to keep retail prices reasonable. Farmers say that releasing these stocks in a season of already low farm-gate prices pushes wholesale rates down further.

- Export uncertainty. India’s onion trade is large, but frequent switches—one season export duty, another season minimum export price, then a change again—made foreign buyers turn to other suppliers for a while. In the year 2022–23, exports were around twenty-five lakh tonnes. Within two years, volumes fell sharply in a season when farmers needed the outlet most.

Result: Auctions at major yards such as Lasalgaon and Vinchur turned weak. Many growers still sit on rabi onions, watching prices fall as quality slowly declines in storage.

How policy choices shaped this crisis

Buffer stocks: a good tool used at the wrong time and place.

The buffer was created to protect households during sudden spikes and to stop hoarding. In a shortage, releasing stock makes sense. In a glut, releasing the same stock in cities that are fed by the very yards where farmers sell simply increases supply and depresses wholesale prices. The lesson is not to scrap the buffer but to change the timing and locations of release: move stock to genuine deficit areas, to fair-price outlets in cities that lack supply, and rebuild buffers quietly during gluts instead of competing with farmers.

Export rules: trust is a market.

Onion buyers abroad want predictability. If rules change mid-season, they build contracts with other countries. When that happens, India loses both price and volume. Farmers and exporters in Maharashtra are therefore asking for one clear export policy for a full rabi-to-kharif season, not rolling changes.

The nature of onion costs.

Onions are labour-intensive and storage-sensitive. After the field is harvested, bulbs must be cured well, kept in airy sheds, graded, and moved at the right time. Losses during storage are real and raise the effective cost. When weather hurts storage, the cost per saleable quintal rises even more.

The marketplace itself.

Most onions still move through regulated wholesale yards. When a glut arrives at the yard gate, prices reflect the worst lot, not the best. Without easy access to alternate buyers, or without the ability to hold stock safely for longer, farmers accept distress prices.

A balanced fix that protects both the kitchen and the kisan

A) Immediate steps

- Stop releasing buffer onions in glut zones. Use the buffer to even prices across districts, not to compete with fresh arrivals. Sell only into retail centres where onions are genuinely short or retail is unreasonably high.

- Announce a season-long export stance. Make one clear rule for the rest of the rabi stock-out and the early kharif months. If domestic arrivals are comfortable and farm-gate prices are below cost, ease exports and fast-track clearances.

- Emergency procurement in the worst-hit blocks. Run a time-bound purchase window at a transparent support price that covers basic cost for ordinary grades. Move the procured stock quickly to deficit states and public kitchens so it does not spoil.

- On-the-ground quality help. Provide grading, drying fans, and transport support at major yards so better onions fetch a better rate even during a glut.

B) System upgrades

- Smart buffer calendar. Publish a rolling two-week plan that shows where buffer will be released, how much, and why. This improves trust and reduces rumours.

- Warehouse receipts for onions. Let farmers store in certified sheds and borrow against receipts, so they are not forced to sell at harvest-time lows.

- Risk-sharing insurance that actually pays. Make quick-pay cover for storage losses and weather shocks a standard feature in onion districts.

- Stable export corridors. Work with railways and ports to fix predictable freight slots and costs for the main export routes to neighbours. The goal is to make exports a pressure valve when domestic prices collapse.

C) Long-term resilience

- Weather-proof storage. Subsidise low-cost ventilated sheds with raised plinths, better roofs, and side vents; promote community sheds where the unit size is too costly for small growers.

- Better data, shared daily. Yard arrivals, grade-wise prices, and buffer positions should be public and updated every day. A single dashboard across states will stop panic and help plan releases and exports.

- Crop planning without coercion. Share clear early signals on area under onion, rainfall trend, and expected arrivals by district. Farmers can then shift area to pulses or vegetables when onion looks headed for a glut.

- Link to nutrition programmes. When prices crash, fresh onions can move to school meals and public kitchens quickly. This saves the crop and improves diets.

The big lessons to carry into the exam hall

- Timing is everything. The same buffer that protects city buyers during spikes must not be used in a way that crushes farm prices during gluts. Release should be targeted by place and time.

- Policy clarity beats policy noise. One steady export stance for a season is worth more than multiple “quick fixes” that scare buyers away.

- Storage is part of income. Farmers earn not just from yield but from how well the bulb survives months of heat and humidity. Weather-proof storage and low-cost working capital are income insurance.

- Transparency is protection. When arrivals, prices, buffer stocks, and export flows are public, panic drops. Traders cannot spread rumours, and government can be judged on facts.

- Balance, not bias. A fair policy protects both sides: households should not face spikes, and growers should not be pushed below cost. The aim is stable, reasonable prices across the year, not extremes.

Exam hook

Onion is the test case for smart price management. In 2025, Maharashtra had surplus arrivals, weather-hit storage, uncertain exports, and buffer releases that kept wholesale rates down in the very cities farmers supply. The fix is timing and trust: hold buffers in glut zones, keep exports predictable for one season, run emergency purchase where prices fall below cost, and repair storage so the next glut is less painful.

Key takeaways

- The protest is about prices far below cost, not just a routine demand.

- Buffer release must be targeted: use it to correct shortages, not to flood markets already in glut.

- Exports need predictability across the rabi-to-kharif window.

- Emergency procurement, warehouse receipts, and weather-proof storage can turn a collapse into a soft landing.

- Open data—arrivals, grade-wise prices, buffer positions, export flows—reduces panic and improves policy.

UPSC Mains Question

- Why did onion prices in Maharashtra crash recently? Explain the role of surplus arrivals, storage damage, export uncertainty, and buffer stock releases. Suggest a balanced policy that protects both farmers’ incomes and consumers’ prices.

Brief hints for answer:

- Causes: bumper crop → oversupply; storage losses; sudden export curbs; buffer release pushing prices down.

- Impact: farm-gate prices below cost; farmer distress; consumer relief short-lived.

- Policy path:

- Short-term relief: direct procurement, quick compensation.

- Stable export policy: avoid sudden bans, seasonal predictability.

- Smarter buffer use: release in lean months, not peak arrivals.

- Storage reforms: modern warehouses, farmer-level cold chains.

- Long-term: diversify crops, promote processing.

- Short-term relief: direct procurement, quick compensation.

UPSC Prelims Question

- Which of the following statements are correct?

- Lasalgaon in Nashik district is a major wholesale market where onion auction prices influence many other markets.

- Rabi onion harvested in March–May is generally better suited for long storage than kharif onion.

- Bangladesh and Sri Lanka are important buyers of Indian onions; swings in these markets influence prices in the Nashik belt.

Options:

(a) 1 and 2 only

(b) 2 and 3 only

(c) 1 and 3 only

(d) 1, 2 and 3

Answer: (d) All three statements are correct.

One-line wrap

Use the buffer like a bridge, not a floodgate; keep export rules steady for a whole season; and back farmers with storage and quick relief—only then will India protect both the field and the family kitchen.

Share This Story, Choose Your Platform!

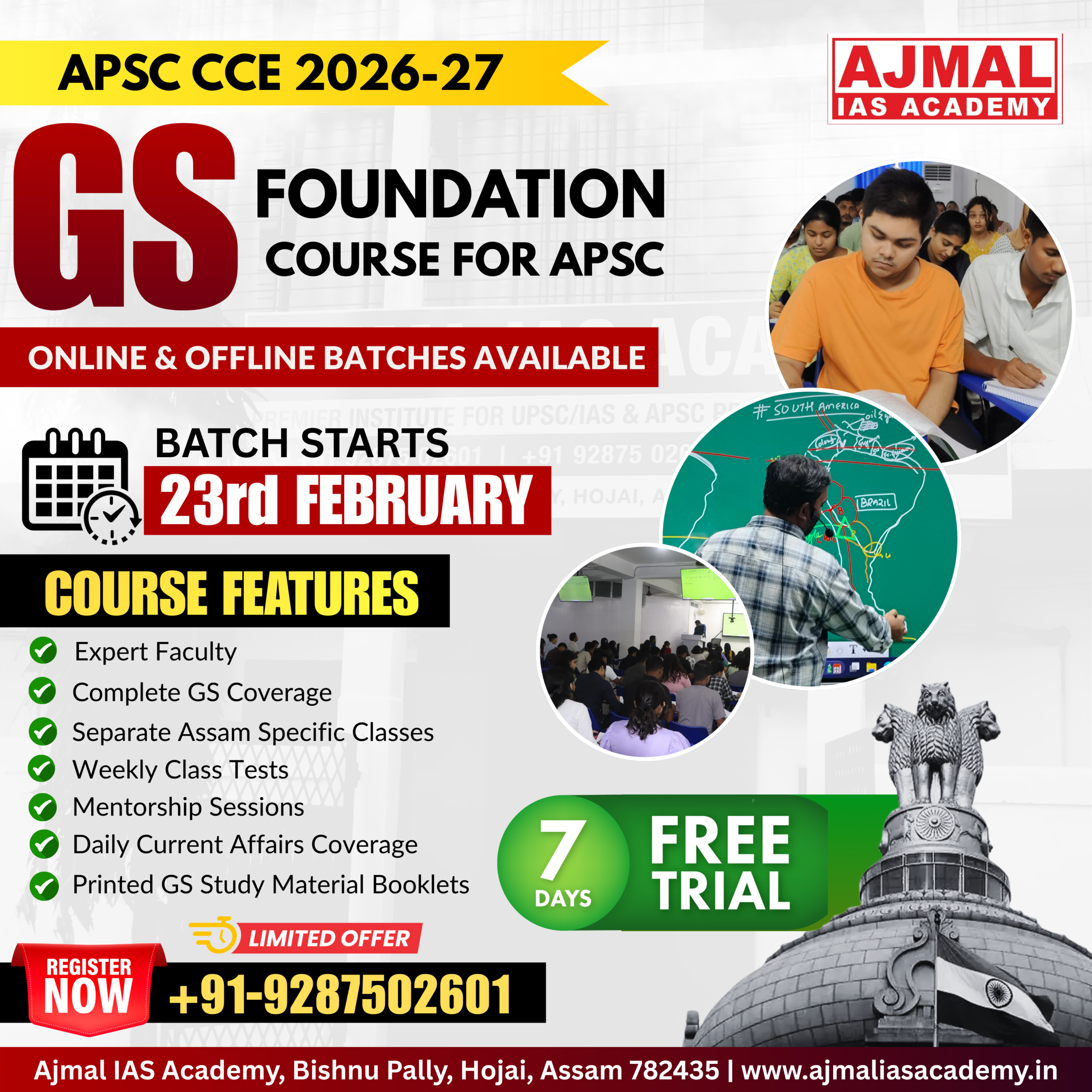

Start Yours at Ajmal IAS – with Mentorship StrategyDisciplineClarityResults that Drives Success

Your dream deserves this moment — begin it here.